What Is the Double Diamond Actually Good For?

Table of Contents

Recently, I attended a startup workshop on the Double Diamond framework—a popular design-thinking model intended to help teams produce better solutions through structured exploration.

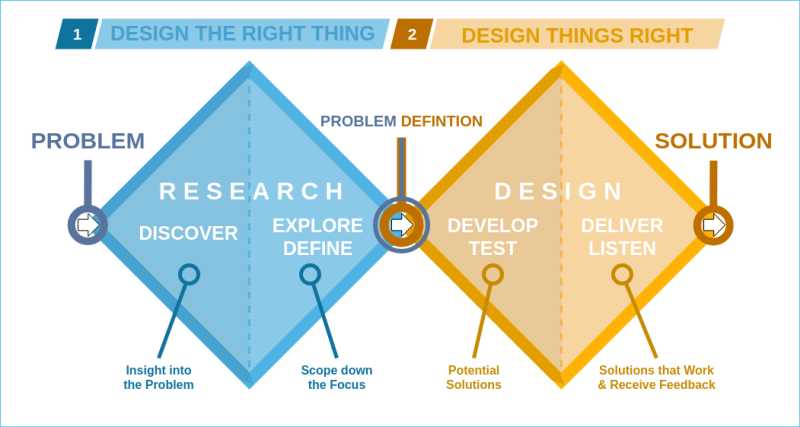

The Double Diamond , developed by the UK Design Council in the mid-2000s, breaks problem-solving into 2 diamonds:

-

The first diamond focuses on understanding the problem through divergent thinking and then narrowing it down through convergent thinking.

-

The second diamond explores possible solutions broadly before converging on one to deliver.

It is widely used in design, product development, and innovation workshops because it is intuitive and collaborative.

There are 4 phases in the whole process:

- Discover

This is where the team conducts user surveys to find out their real problems

- Define

The team then drills down on a single problem to tackle.

- Develop

The team brainstorms ideas for that problem.

- Deliver

The ideas are then distilled into a single prototype to solve that single problem.

The Problem with Group Convergent Thinking

However, in practice, it has critical flaws in the convergent phases as:

- the Define phase of the first diamond and

- the Deliver phase of the second

In the workshop, the “problem” was defined largely by the design team’s own assumptions rather than by what users actually said.

Although user research was conducted, the team selectively interpreted it to fit their existing biases . As a result, the group ended up designing solutions to their version of the problem, not the users’ real one.

This flaw compounded in the Deliver phase.

Users were asked to evaluate solutions that didn’t meaningfully address their original pain points. When feedback didn’t align, the team pushed forward anyway instead of looping back to redefine the problem.

Iterating this process simply turned users into validators of a non-problem.

This is why the Double Diamond is potentially wasteful .

Unrealistic Solutions that Cater to the Problem Solver Instead of the Actual Problem

A real-world analogy is the solution of carbon credits.

Policymakers often define climate change primarily as a taxation problem because taxation is the tool they know best.

Yet broad emissions taxes tend to stall due to economic resistance.

The true solution relies on engineering and chemistry, not finance or taxation.

These should be tailored to individual factories, farms, and industries instead of being a one-size fits all solution.

A Better Framework

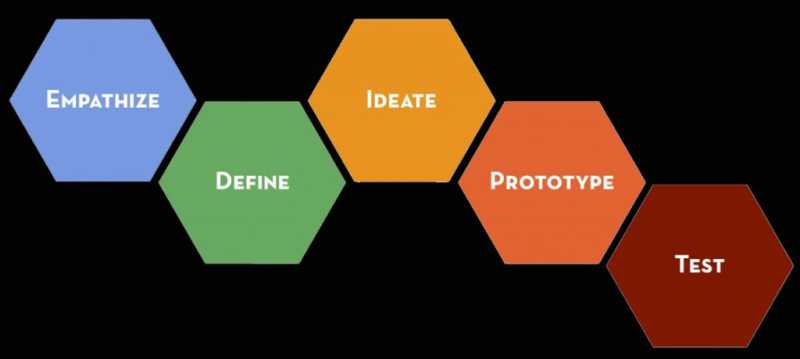

In contrast, the Stanford d.school design thinking model—popularized by David Kelley—handles this better.

It emphasizes rapid prototyping early, even when the problem is still unclear.

By building a prototype for an assumed problem, teams often discover that their initial framing was wrong.

This insight then informs a better second prototype, creating a tighter feedback loop between problem and solution.

This fast, integrated approach works especially well for complex, technical, or domain-specific challenges.

We can say that:

- the Double Diamond is an example of silo thinking that splits problem and solution – this is from the industrial revolution which focuses on the rigidity of mechanics

- the d.school model is an example of integrated thinking that combines both – this is from the information revolution which focuses on flow

The Double Diamond is for Group Feeling

That said, the Double Diamond is not useless—it’s just not primarily a solution engine.

Its real strength lies in exposing team dynamics because it relies on divergent and convergent group activities.

This reveals:

- who dominates discussion

- who influences decisions

- who hesitates

- who brings creative insight

In that sense, it functions as a form of organizational intelligence.

For example, a sales manager might pose a broad challenge like “increase sales.”

During the Discover phase, teams bring up sub-problems such as:

- lead generation, or

- brand positioning

- promotions

- key account focus

In Define and Develop, they align on priorities and test ideas with a small customer group in Deliver.

The outcomes can then be compared with strategies proposed by external consultants to evaluate whether internal team thinking adds value.

In short, the Double Diamond is better as a team-building and diagnostic tool, instead of being a reliable framework for solving complex, real-world problems.

Its value lies less in the solutions it produces and more in what it reveals about how teams think, decide, and work together.