DSIT and Historical Economic Problems

Table of Contents

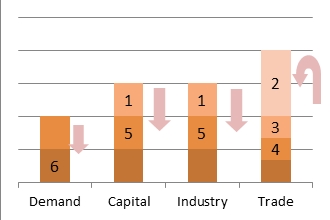

The DSIT shows that the imbalances of the real values in capital, industry, and trade, in relation to demand, result in economic problems:

The Great Depression: High Value, Low Trade

Improvements in technology increased the productive capital (Bar 1) in the 1920’s, creating industries that led to the prosperity of the Roaring Twenties.

Unfortunately, the prosperity emboldened the selfish hand to pursue more profits through speculative stock trading in 1928 and the creation of tariffs in 1930.

Stock speculation (Bar 2) resulted in the overtrading of stocks leading to the rapid growth and eventual crash of the stock market, a phenomenon known by Adam Smith:

When the profits..happen to be greater than ordinary, over-trading becomes a general error both among great and small dealers. They..buy upon credit..an unusual quantity of goods, which they send to some distant market in hopes that the returns will come in before the demand for payment. The demand comes before the returns, and they have nothing at hand..

Adam Smith

Book 4, Chapter 1, Par. 16

The Crash of 1929 destroyed most of the nominal capital in the economy. Although serious, it could not lead to a depression as productive capital was still present.

However, the sudden scarcity of money (Bar 3) reduced the circulation of goods and services (internal trade) while the tariffs of 1930 (Bar 4) reduced international (external) trade which eventually lowered the productive capital and industry (Bar 5) as well.

Left uncorrected, low trade and low value caused demand to decline (Bar 6) which further dragged down trade and value, creating negative iterations culminating in a Great Depression.

The correct solution was to repeal the tariffs, and, as Milton Friedman pointed out (Federal Reserve Board, 2004), to prop up money supply (trade).

Increasing the money supply or the “great wheel of circulation”, according to Smith, is necessary to support productive capital in a society as industry increases, which is what happened during the Roaring Twenties.

Unfortunately, the inexperience of the Fed made such a solution impossible at that time. Keynes found an indirect solution of increasing trade through deficit spending, which restored demand, reversing the process.

Latin American Debt Crisis: Low Value, High Trade

- Latin America in the 1970’s needed economic development to build capital to address its many needs.

- Large loans were given out, which unfortunately, were lost to corruption and did not go to build productive capital and industry.

- The interests piled up which caused further strain on money (trade).

The solution would have been to ‘reboot’ the problem – cancel the old debts (Batra, 1989), wholly or partially, and start new loans with more oversight.

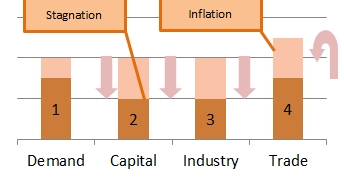

1970’s Stagflation: Low Value, High Trade

In 1944, the Bretton Woods system made a fatal mistake of setting the US dollar, backed by US gold, as its reserve currency, instead of the bancor, backed by multilateral barter.

By doing so, the US fell into a “get-rich-quick” trap—becoming an economic superpower but opening up the floodgates of global overtrading.

This global overtrading took the form of Eurodollars which, in 1971, grew to threaten US gold reserves, leading to the Nixon Shock.

This shock added to inflation (1) while the Oil Crisis reduced productive capital (2). The spending for the Vietnam War, which in the Keynesian paradigm was supposed to solve the problem, did not work as it did not go to build productive industries or technology.

Paul Volcker’s sudden increase in interest rates solved inflation (4) but caused a recession as it ‘rebooted’ the economy to its real value-level.

As stagflation is primarily a capital problem, the best solution was to increase productive capital (Sachs, 2008) by reducing taxes on productive industries or increasing spending to encourage them.

The Reagan tax cuts of 1981 (Congressional Budget Office, 1986) fulfilled this need and led to recovery. Unfortunately, prolonged cuts will eventually result in overtrading due to the selfish-interest dogma. Chronic overtrading led to the new imbalances that were seen in the Dot Com bubble, Housing bubble, and 2008 Financial Crisis.

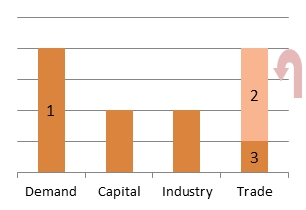

Enron Collapse: Low Value, High Trade

The Value-Trade theory applies to microeconomics as well as macroeconomics. In the case of Enron, low interest rates gave the liquidity needed (1) for investors to purchase its stock.

As the stock was overvalued by “cooking the books” (2), the low productive capital could not sustain the returns demanded and led to bankruptcy.

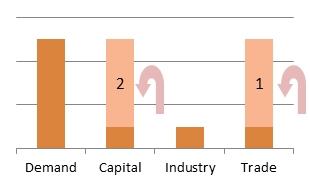

The 2008 Financial Crisis: Low Value, High Trade

Unregulated collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) created through securitization, on top of a fiat economy, caused an increase in phantom liquidity for banks (1) and phantom capital for the investors that bought them. This phantom capital became the next target of the selfish hand.

- The Crash of 1929 was promoted by Irving Fisher and American banks.

- The Dot-com bubble was promoted by Henry Blodget (Ackman, 2003).

- The Housing bubble was promoted by Robert Kiyosaki (Lloyd, 2005).

The 2008 Financial Crisis used new phantom capital which was promoted by behemoth financial institutions to a global audience.

Since capital is used to create value and not an end in itself, such phantom capital could not create real value and vanished in a “credit crunch” as quickly as it could be erased by the bookkeeper’s pen (2).

The “credit crunch” destroyed the phantom trade to its real levels, which in turn, also destroyed the nominal value it created. The “crunch” has been described many times by Smith:

Over-trading is the common cause of it (scarcity of money). Sober men, whose projects have been disproportioned to their capitals..have neither wherewithal to buy money nor credit to borrow it, as prodigals whose expence has been disproportioned to their revenue. Before their projects can be brought to bear, their stock is gone, and their credit with it.

Adam Smith

Book 4, Chap. 1, Par. 16

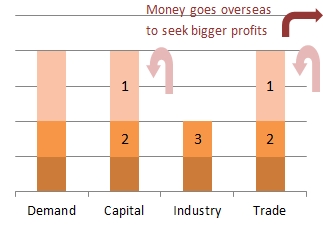

As much of the liquidity was used to move productive value overseas (3) to maximize profits, both the monetary (quantitative easing) and fiscal spending (Keynesian) attempts of the US and Europe to re-invigorate businesses in their own countries have failed to guarantee recovery.

The solution is to create regulation and fiscal measures to break down huge banks and corporations, force productive capital back to their home markets, and to restrain speculative trading.

2012 Japanese Economy: Low Demand, High Trade

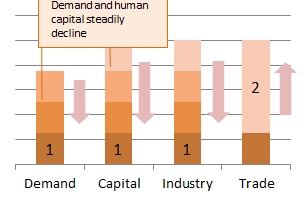

As “the general industry of the society can never exceed what the capital of the society can employ”, Japan’s declining population gradually reduces the demand and human capital needed to sustain its industries (1), causing an exodus of manufacturers and lower competitiveness (World Economic Forum, 2012).

The Bank of Japan’s quantitative easing (Evans-Pritchard, 2012) props up trade (2) but does not address the fundamental problems of low demand and shrinking labor force which has been declining since 1998 (Statistics Bureau, 2012), and so, the economy still does not grow.

The solution is to gradually, not suddenly, increase demand by expanding its market through closer economic integration with other countries, at the expense of its farmers (Tabuchi, 2010) and to open up foreign immigration just as Israel and Singapore have done.