Descartes' Theory of the Aether

Table of Contents

According to Descartes’ theory, the sun is the centre of an immense vortex formed of the first or subtlest kind of matter.[4]

The vehicle of light in space is a 2nd kind of matter, composed of closely packed globules of a size between that of the vortex-matter and that of ponderable matter.

The globules of the 2nd element, and all the matter of the 1st element, are constantly straining away from the centres around which they turn due to the centrifugal force of the vortices[5].

This presses the globules with each other. They tend to move outwards, although they do not actually so move.[6] The transmission of this pressure constitutes light.*

Superphysics Note

The action of light therefore extends on all sides around the sun and fixed stars, and travels instantaneously to any distance.[7]

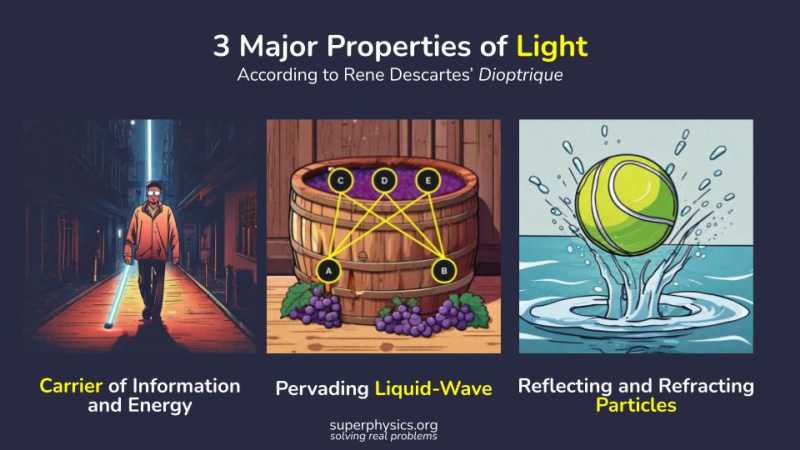

In the Dioptrique,[8] vision is the perception of objects which a blind man obtains by using a stick.

The transmission of pressure along the stick from the object to the hand is like the transmission of pressure from a luminous object to the eye by the 2nd kind of matter.

The diversities of colour and light are from the different ways in which the matter moves.[9]

In the Météores,[10] the various colours are connected with different rotatory velocities of the globules.

- The particles which rotate most rapidly give off red

- The slower ones give off yellow

- The slowest ones give off green and blue

This is the order of colours from the rainbow.

The assertion of the dependence of colour on periodic time is a curious foreshadowing of one of the great discoveries of Newton.

These principles were amplified by a more particular discussion of reflection and refraction.

The law of reflecton is that the angles of incidence and refraction are equal.

- This was known to the Greeks.

The law of refraction is that the sines of the angles of incidence and refraction are to each other in a ratio depending on the media.

- This was published for the first time.[11]

Descartes gave it as his own.

But he seems to have been under considerable obligations to Willebrord Snell (b. 1591, d. 1626), Professor of Mathematics at Leyden, who had discovered it experimentally in 1621.

Snell did not publish his result, but communicated it in manuscript. Huygens affirms that this manuscript had been seen by Descartes.

Descartes presents the law as a deduction from theory.

- This, however, he is able to do only by the aid of analogy.

When rays meet ponderable bodies, “they are liable to be deflected or stopped in the same way as the notion of a ball or a stone impinging on a body”.

- “The inclination for light to move should follow in this the same laws as motion."[12]

Thus he replaces light, whose velocity of propagation he believes to be always infinite*, by a projectile whose velocity varies from one medium to another.

Superphysics Note

Next is the law of refraction[11]:

Let a ball thrown from A meet at B a cloth CBE, so weak that the ball is able to break through it and pass beyond, but with its resultant velocity reduced in some definite proportion, say 1 : k.

Then if BI be a length measured on the refracted ray equal to AB, the projectile will take k times as long to describe BI as it took to describe AB.

But the component of velocity parallel to the cloth must be unaffected by the impact. Therefore the projection BE of the refracted ray must be k times as long as the projection BC of the incident ray. So if i and r denote the angles of incidence and refraction, we have:

…

or the sines of the angles of incidence and refraction are in a constant ratio.

This is the law of refraction.

Descartes wanted to include all known phenomena in his system. He devoted some attention to a class of effects which were little thought of back then, but which were destined to play a great part in the subsequent development of Physics.

The ancients knew the curious properties possessed by two minerals:

- Aamber (ἣλεκτρον)

When amber is rubbed, it attracts lightweight bodies.

- Magnetic iron ore (ἡ λίθος Μαγνῆτις).

This attracts iron.

The use of the magnetic compass at sea was not derived from classical antiquity. But it was certainly known in the time of the Crusades.

Petrus Peregrinus and the European Discovery of Magnetism

Magnetism was one of the few sciences which progressed during the Middle Ages. In the 13th century, Petrus Peregrinus,[13] a native of Maricourt in Picardy discovered it.*

Superphysics Note

He took a natural magnet or lodestone, rounded into a globular form. He laid it on a needle, and marked the line along which the needle set itself.

- Then laying the needle on other parts of the stone, he obtained more lines in the same way.

When the entire surface of the stone had been covered with such lines, they formed circles, which girdled the stone in exactly the same way as meridians of longitude girdle the earth.

There were 2 points at opposite ends of the stone through which all the circles passed, just as all the meridians pass through the Arctic and Antarctic poles of the earth.[14]

Struck by the analogy, Peregrinus proposed to call these two points the poles of the magnet. He observed that the way in which magnets set themselves and attract each other depends solely on the position of their poles, as if these were the seat of the magnetic power.

Such was the origin of those theories of poles and polarization which in later ages have played so great a part in Natural Philosophy.