Images That Form On The Back Of The Eye

Table of Contents

In order to feel, the soul does not need to contemplate any images which are similar to the things it feels.

The objects that we look at impress quite perfect images in the depths of our eyes.

This is similar to a completely closed room with a single hole with a glass lens in front of this hole.

- Behind it is spread at a certain distance a white cloth on which the light, which comes from objects outside, forms these images.

They say that:

- this room represents the eye

- this hole represents the pupil

- this glass represents the crystalline humor, or rather all those parts of the eye which cause some refraction

- this linen represents the inner skin which is composed of the ends of the optic nerve.

Take the eye of a freshly dead man.

Cut away the 3 membranes that surround it, so that a large part of the humor M, which is inside, remains exposed, without any of it spilling out.

Then, having covered it with some white substance, such as a piece of paper or an eggshell, RST, which is so thin that light can pass through it.

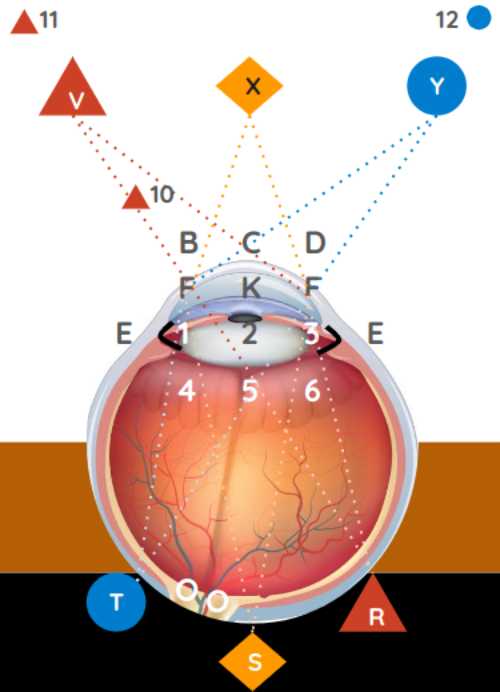

You place this eye in a specially made window, Z, so that the front, BCD, faces toward some location where there are various objects, such as V, X, Y, illuminated by the sun.

The back, where the white substance RST is, faces inward toward the chamber, P, where you are.

No light should enter, except that which can pass through this eye, of which you know that all the parts, from C to S, are transparent.

Then look at the white substance RST.

You will see a painting that represents all the objects that are outside toward VXY.

If you press it too much or too little, this painting will become less distinct.

One must press it a bit harder and stretch its shape a bit longer when the objects are very close, than when they are farther away.

From each point of the objects V, X, Y, there enter into this eye as many rays that penetrate up to the white body RST, as the opening of the pupil FF can comprehend.

Both from the nature of refraction and from that of the 3 humors K, L, M, all those rays that come from the same point are bent in crossing the three surfaces BCD, 123, and 456, in the manner required to gather again around a single point.

One must render the figure of this eye a bit longer when the objects are very close than when they are farther away.

There enter into this eye many rays from each point of the object.

For the painting to be as perfect as possible, the figures of these 3 surfaces must be such that all the rays coming from one point of the objects converge exactly at one point of the white body RST.

As you can see here:

- those from point

Xconverge at pointS. - those from point

Vconverge at pointR. - those from point

Yconverge at pointT

Reciprocally:

- no rays come towards

S, except from pointX - nor towards

R, except from pointV - nor towards

T, except from pointY - and so on for the others.