The Marshallian Supply and Demand Fallacy

This is the early version of my Fallacy of Market Equilibrium Post that was sent to a journal but was not accepted. This led me to post to the internet instead.

Juan

The Cause of Crises

The arbitrariness created by selfish interests, combined with the impossibility of knowing everything, allows nominal value to be created from nowhere, just as easily as they can be written by a “bookkeeper’s pen” (Friedman, 1969).

This lets such value vanish just as quickly during periods of value-correction called crashes and recessions.

Such a system resembles a game with players competing for points in the form of money.

All games must have winners and losers, and are never satisfied with a draw. Thus, even if buyers and sellers may come to an agreement or “equilibrium” (a draw), sellers will still endeavor to win and create imbalance to their advantage.

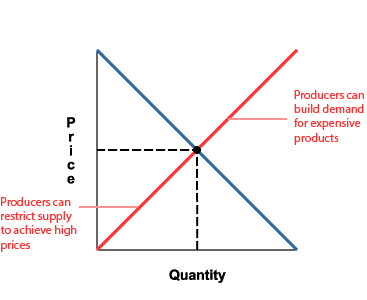

The lack of a measure of real value corrupts the game by allowing profiteers (powerful players) to conspire to command nominal prices (points) or regulations (in-game rules) through bribing, lobbying, hoarding, inducing scarcity, and exploitation of workers by their masters:

What are the common wages of labour, depends every where upon the contract usually made between those two parties, whose interests are by no means the same. The workmen desire to get as much, the masters to give as little as possible. The former are disposed to combine in order to raise, the latter in order to lower the wages of labour. It is not, however, difficult to foresee which of the two parties must, upon all ordinary occasions, have the advantage in the dispute, and force the other into a compliance with their terms…

Adam Smith

WN Book 1, Chap. 8, Pars. 10-13

In all such disputes the masters can hold out much longer… Masters are always and every where in a sort of tacit, but constant and uniform combination, not to raise the wages of labour above their actual rate…Masters too sometimes enter into particular combinations to sink the wages of labour even below this rate. These are always conducted with the utmost silence and secrecy, till the moment of execution, and when the workmen yield, as they sometimes do, without resistance, though severely felt by them, they are never heard of by other people.

Adam Smith

WN Book 1, Chap. 8, Pars. 10-13

This game was then visualized through Alfred Marshall’s Partial Equilibrium, which became the foundation of microeconomics.

In this theory, the lack of any concrete measure of value is offset by the fact that buyers and sellers would somehow find “equilibrium” prices all the time if everything else stays the same (ceteris paribus) every time.

This was a fallacy that was known to many intellectuals in the 1700’s, especially Adam Smith:

Nothing, however, can be more absurd than this whole doctrine of the balance of trade, upon which, not only these restraints, but almost all the other regulations of commerce are founded. When two places trade with one another, this doctrine supposes that, if the balance be even, neither of them either loses or gains; but if it leans in any degree to one side, that one of them loses and the other gains in proportion to its declension from the exact equilibrium. Both suppositions are false. A trade which is forced by means of bounties and monopolies may be and commonly is disadvantageous to the country in whose favour it is meant to be established, as I shall endeavour to show hereafter. But that trade which, without force or constraint, is naturally and regularly carried on between any two places is always advantageous, though not always equally so, to both.

Adam Smith

WN, Book 4, Chap 3. Par. 31, emphasis added

To Smith, the “Law of Demand” need not follow any mathematical equilibrium. He blames vested interests for its corruption:

In every country it always is and must be the interest of the great body of the people to buy whatever they want of those who sell it cheapest. The proposition is so very manifest that it seems ridiculous to take any pains to prove it; nor could it ever have been called in question had not the interested sophistry of merchants and manufacturers confounded the common sense of mankind. Their interest is, in this respect, directly opposite to that of the great body of the people.

Adam Smith

Par. 39, emphasis added

As the “Law of Demand” is independent of any equilibrium, it is therefore the “Law of Supply” that is subordinate and dependent on it:

Consumption is the sole end and purpose of all production; and the interest of the producer ought to be attended to only so far as it may be necessary for promoting that of the consumer. The maxim is so perfectly self-evident that it would be absurd to attempt to prove it. But in the mercantile system the interest of the consumer is almost constantly sacrificed to that of the producer; and it seems to consider production, and not consumption, as the ultimate end and object of all industry and commerce.

Adam Smith

Chap. 8, Par. 49, emphasis added

A free society, one that is not controlled by vested interests, thus has an independent demand curve. The subjective and arbitrary valuations of producers, represented by the wages and profits they desire, are contained in the producer’s selling price, which Smith calls the “natural price”:

When the price of any commodity is neither more nor less than what is sufficient to pay the rent of the land, the wages of the labour, and the profits of the stock employed in raising, preparing, and bringing it to market, according to their natural rates, the commodity is then sold for what may be called its natural price.

Adam Smith

Book 1, Chap. 7, Par. 4

This has a qualitative measure (high or low price), distilled into the simple equation:

Non-arbitrary (production cost) + Semi-arbitrary (rent, wages and profits) = Natural Price

Unlike the natural price which is qualitative (y-axis), the market price (the price perceived by buyers who are always seeking the lowest price), is quantitative (x-axis):

The market price of every particular commodity is regulated by the proportion between the quantity which is actually brought to market, and the demand of those who are willing to pay the natural price of the commodity, or the whole value of the rent, labour, and profit, which must be paid in order to bring it thither.

Adam Smith

Pars. 7 & 8

Free competition reduces the arbitrariness of wages and profits, allowing natural prices to fall to the lowest level demanded by society, and thus satisfy all, both sellers and buyers:

It is the interest of all those who employ their land, labour, or stock, in bringing any commodity to market, that the quantity never should exceed the effectual demand; and it is the interest of all other people that it never should fall short of that demand. (Par. 12). The price of monopoly is upon every occasion the highest which can be got. The natural price, or the price of free competition, on the contrary, is the lowest which can be taken, not upon every occasion indeed, but for any considerable time altogether. The one is upon every occasion the highest which can be squeezed out of the buyers, or which, it is supposed, they will consent to give: The other is the lowest which the sellers can commonly afford to take, and at the same time continue their business.

Adam Smith

Par. 27

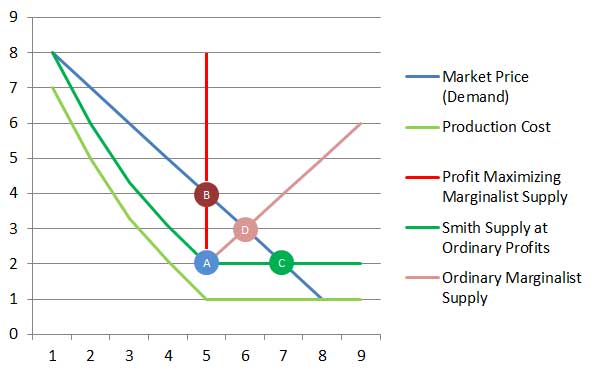

The graph below shows Marshall’s supply curves (red lines) and Smith’s Natural Price supply curves (green lines).

Let us say one baker sees a demand for donuts.

He produces 5 units at a “natural” selling price of $2 each (light green line). This includes an ordinary arbitrary profit of $1 per unit which he is satisfied with, on top of the production cost (green line).

He finds that all of his donuts are sold (Point A).

He then has two choices:

- Increase the price or

- Increase the quantity sold

If he has a selfish or monopolistic interest, he will slowly raise prices, or do “groping” until he finds the highest price with which he can sell all 5 donuts without inviting competition. This is the monopolistic price (vertical red line at Point B).

In such a case, competition will sooner or later emerge which will force him to lower his price to $3 (Point D).

Most commonly, and more naturally, he will produce more donuts until all demand is satisfied. In this case, it is between 7-8 units with ordinary (Point C) or even no profits (where the green lines intersect with the blue demand line), lest the demand be satisfied by competitors or his customers complain of his frequently-changing prices.

A profit-maximizing marginalist baker would bake 5 donuts and price them at $4 each, for a total profit of $15 (54, less 51). This benefits a total 6 people (including himself).

A socially-minded baker, on the other hand, would bake 7 donuts at a price of $2 each, for a total profit of $7 (72 less 71), benefiting a total of 8 people in his society, or all the people interested in donuts.

Adam Smith’s supply curve would therefore benefit more people and address all demand without compromising product quality, at the expense of lesser profits at ordinary rates.

| Seller | Quantity Served | Profit to Baker | People Benefited |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marginalist with Monopoly | 5 | $15 | 6 |

| Marginalist with Competition | 6 | $12 | 7 |

| Socially-minded Baker | 7 | $7 | 8 |

If applied in a bigger scale, this would support his assertion that the earth’s resources would be able to benefit all humans if allocated in a socially-minded way:

The produce of the soil maintains at all times nearly that number of inhabitants which it is capable of maintaining..When Providence divided the earth among a few lordly masters, it neither forgot nor abandoned those who seemed to have been left out in the partition. These last too enjoy their share of all that it produces.

Adam Smith

TMS, Part 4, Par. 10

Instead of being in equilibrium, Smith’s market prices are realistically flexible, being either “above (high profits), or below (low profits), or exactly the same with its natural price (ordinary profits)”:

The market price of any particular commodity, though it may continue long above, can seldom continue long below, its natural price. (Chap. 7, Par. 30) Profit is so very fluctuating, that the person who carries on a particular trade cannot always tell you himself what is the average of his annual profit. It is affected, not only by every variation of price in the commodities which he deals in, but by the good or bad fortune both of his rivals and of his customers, and by a thousand other accidents to which goods when carried either by sea or by land, or even when stored in a warehouse, are liable. It varies, therefore, not only from year to year, but from day to day, and almost from hour to hour. To ascertain what is the average profit of all the different trades carried on in a great kingdom, must be much more difficult; and to judge of what it may have been formerly, or in remote periods of time, with any degree of precision, must be altogether impossible..

Adam Smith

Chap. 9, Par. 3

As Capitalism is based purely on profits which are unstable by nature, “uncertainty” or “not knowing the future” becomes an unnecessarily big issue in current economics.

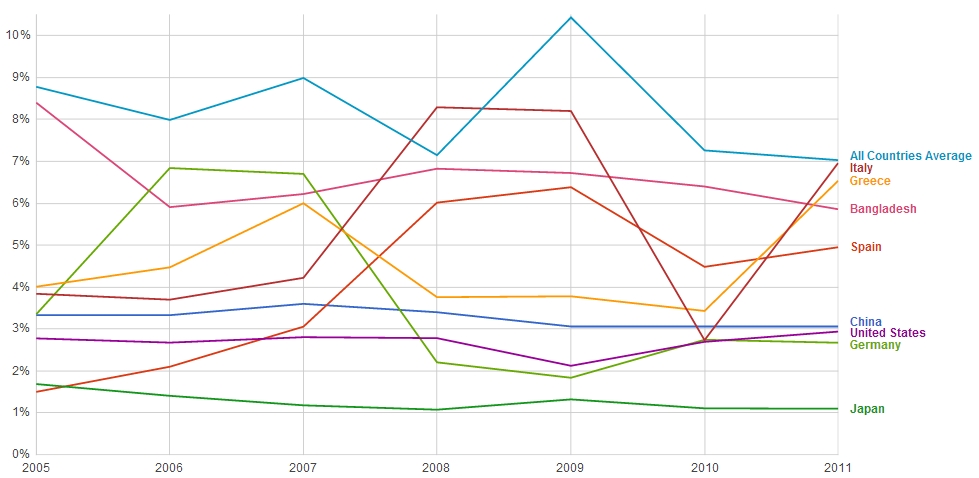

The Inverse Relationship of Development and Profits

To Smith, one of the things certain about profits is that there is an inverse relationship between the profits of merchants and the wealth of societies:

In a country which had acquired its full complement of riches, where in every particular branch of business there was the greatest quantity of stock that could be employed in it, as the ordinary rate of clear profit would be very small, so that usual market rate of interest which could be afforded out of it, would be so low as to render it impossible for any but the very wealthiest people to live upon the interest of their money. (Par. 20) When profit diminishes, merchants are very apt to complain that trade decays; though the diminution of profit is the natural effect of its prosperity, or of a greater stock being employed in it than before.

Adam Smith

Par. 10, emphasis added

| Status | Country | Market Interest Rate in 1700’s |

|---|---|---|

| Fast Advancing* | Holland | 2-3% |

| Advancing | Englahd | 3-5% |

| Slowly Advancing | France | 5% |

- early in the mercantile period

| Status | Country | Change in Interest Rate Spread 2005 vs 2012 |

|---|---|---|

| Advancing | Bangladesh | -2.54 |

| Slowly Advancing | Germany | -0.68 |

| Slowly Advancing | Japan | -0.59 |

| Slowly Advancing | China | -0.29 |

| Stagnating | US | +0.16 |

| Declining | Italy | +3.12 |

| Declining | Spain | +3.45 |

| Rapidly Declining | Zimbabwe (2005-2009) | +281.75 |

As free competition produces the lowest profits, selfish-interests find themselves trying lower their costs below the ordinary rates by:

- lowering wages, evading taxes, fighting regulation, causing negative externalities, etc, or

- raising prices through monopoly by lobbying for unfair advantages, acquiring smaller competitors, and enforcing what Smith calls “secrets in manufactures” such as intellectual property and information asymmetry.

The best and most sustainable way to raise profits then, as today, was through innovation and the expansion to new markets:

The acquisition of new territory, or of new branches of trade, may sometimes raise the profits of stock, and with them the interest of money, even in a country which is fast advancing in the acquisition of riches…Part of what had before been employed in other trades, is necessarily withdrawn from them, and turned into some of the new and more profitable ones.

In all those old trades, therefore, the competition comes to be less than before. The market comes to be less fully supplied with many different sorts of goods. Their price necessarily rises more or less, and yields a greater profit to those who deal in them, who can, therefore, afford to borrow at a higher interest….The great accession both of territory and trade, by our acquisitions in North America and the West Indies, will sufficiently account for this..

Adam Smith

Book 1, Chap. 9, Par 12

Unfortunately, selfish-interests would rather raise prices by establishing corporate monopolies:

It is to prevent this reduction of price, and consequently of wages and profit, by restraining that free competition which would most certainly occasion it, that all corporations, and the greater part of corporation laws, have been established.

Adam Smith

Chap.10, Par.72

and by going against the interests of the rest of society, even to the point of oppression:

The..annual produce of..every country..constitutes a revenue to three different orders of people; to those who live by rent, to those who live by wages, and to those who live by profit. These are the three great..orders of every civilized society, from whose revenue that of every other order is ultimately derived…The interest of this third order.. has not the same connection with the..interest of the society as that of the other two…The interest of the dealers..is always..different from..that of the public. To widen the market and to narrow the competition, is always the interest of the dealers.

Adam Smith

Book 1, Chap. 2, Par. 264, emphasis added

To widen the market may frequently be agreeable enough to the interest of the public; but to narrow the competition must always be against it, and can serve only to enable the dealers, by raising their profits above what they naturally would be, to levy, for their own benefit, an absurd tax upon the rest of their fellow-citizens.

The proposal of any new law or regulation of commerce which comes from this order, ought always to be listened to with great precaution, and ought never to be adopted till after having been long and carefully examined, not only with the most scrupulous, but with the most suspicious attention. It comes from an order of men, whose interest is never exactly the same with that of the public, who have generally an interest to deceive and even to oppress the public, and who accordingly have, upon many occasions, both deceived and oppressed it.

Adam Smith

Book 1, Chap. 2, Par. 264

| Law | Cause | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act | Lobbying by American Farmers | Fueled the Great Depression |

| Plaza Accord | Lobbying by Caterpillar | Japan Asset Price Bubble |

| Repeal of Glass-Steagal | Lobbying by Citigroup | Subprime Crisis |

Thus, Smith clearly shows that the interests of corporations and those who live by profit are against the interests of societies, something that the ancient Chinese knew, and perhaps was the reason why they regarded the merchant class as the lowest class in Chinese society:

In China and Indostan accordingly both the rank and the wages of country labourers are said to be superior to those of the greater part of artificers and manufacturers. They would probably be so every-where, if corporation laws and the corporation spirit did not prevent it.

Adam Smith

WN, Book 1, Chap. 10, Par. 79

A supply curve with a social outlook chases demand, new markets, and encourages production and innovation unlike Marshall’s supply curve which stifles competition, withholds production, or coaxes demand to buy at higher prices. Smith’s supply curve will look like a production cost curve in the short run, and a Keynesian supply curve in the long run as business interests will be in line with the interest of societies and governments.

Because of the corruption of the “law” of demand and supply, people who follow the current economic theory struggle against each other:

By such maxims as these, however, nations have been taught that their interest consisted in beggaring all their neighbours. Each nation has been made to look with an invidious eye upon the prosperity of all the nations with which it trades, and to consider their gain as its own loss. Commerce, which ought naturally to be, among nations, as among individuals, a bond of union and friendship, has become the most fertile source of discord and animosity.

Adam Smith

Par. 38

As this “absurd doctrine” is unnatural, it has necessitated the creation of unrealistic concepts such as “perfect rationality”, “perfect competition”, and “perfect information” and created economic puzzles (Obstfeld and Rogoff, 2001).

Economists blame the public for “irrational exuberance” and accuse the government of not allowing perfect competition or companies for “information asymmetry” even though no economist has been able to give any real solutions even in this age of supercomputers.

In reality, the doctrines of the marginal revolution created arbitrariness simply to allow profit maximization so that each person can realize one’s pleasures more quickly while disregarding its negative effects on others, a symptom present among selfish people.

Had there been a real measure of value, with empowerment and free competition, then the realization of one’s pleasures would have been delayed by the natural course of commerce, dependent on many other factors.

The marginalists created mathematical “get-rich-quick” supply curves that, instead of producing the most quantity to satisfy demand, focuses merely on taking advantage of the numerical gap between high and low prices, something that merchants naturally do.

Such a mercantile system expectedly creates a few big winners, many losers, rapid economic booms, and severe busts, all in a climate of animosity—a system now called Capitalism.

There is no great secret in fortune making. All you do is buy cheap and sell dear, act with thrift and shrewdness and be persistent.

Hetty-Green

The Witch of Wall Street