The Sons of Enki

Table of Contents

Of the 6 known sons of Enki, three have been featured in Sumerian tales:

- The firstborn Marduk, who eventually usurped the supremacy

- Nergal, who became ruler of the Lower World

- Dumuzi, who married Inanna/lshtar.

Enlil, too, had 3 sons who played key roles in both divine and human affairs:

- Ninurta was born to Enlil by his sister Ninhursag and so was the legal successor

- Nanna/Sin, firstborn by Enlil’s official spouse Ninlil

- a younger son by Ninlil named ISH.KUR (“mountainous,” “far mountain land”), who was more frequently called Adad (“beloved”).

As brother of Sin and uncle of Utu and Inanna, Adad appears to have felt more at home with them than at his own house. The Sumerian texts constantly grouped the 4 together.

The ceremonies connected with the visit of Anu to Uruk also spoke of the four as a group. One text, describing the entrance to the court of Anu, states that the throne room was reached through “the gate of Sin, Shamash, Adad, and Ishtar:’ Another text, first published by V. K. Shileiko (Russian Academy of the History of Material Cultures) poetically described the four as retiring for the night together.

The greatest affinity seems to have existed between Adad and Ishtar, and the two were even depicted next to each other, as on this relief showing an Assyrian ruler being blessed by Adad (holding the ring and lightning) and by Ishtar, holding her bow. (The third deity is too mutilated to be identified.) (Fig. 55)

Was there more to this “affinity” than a platonic relationship, especially in view of Ishtar’s “record”?

In the biblical Song of Songs, the playful girl calls her lover dod-a word that means both “lover” and “uncle.” Now, was Ishkur called Adad—a derivative from the Sumerian DA.DA—because he was the uncle who was the lover?

Ishkur was a playboy, mighty god, endowed by his father Enlil with the powers and prerogatives of a storm god.

As such he was revered as the Hurrian/Hittite Teshub and the Urartian Teshubu (“wind blower”), the Amorite Ramanu (“thunderer”), the Canaanite Ragimu (“caster of hailstones”), the IndoEuropean Buriash (“light maker”), the Semitic Meir (“he who lights up” the skies). (Fig. 56)

A god list kept at the British Museum, as shown by Hans Schlobies (Der Akkadische Wettergott in Mesopotamien), clarifies that Ishkur was indeed the divine lord in lands far from Sumer and Akkad. As Sumerian texts reveal, this was no accident. Enlil, it seems, willfully dispatched his young son to become the “Resident Deity” in the mountain lands north and west of Mesopotamia.

Why did Enlil dispatch his youngest and beloved son away from Nippur?

Several Sumerian epic tales have been found about the arguments and even bloody struggles among the younger gods. Many cylinder seals depict scenes of god battling god (Fig. 57); it would seem that the original rivalry between Enki and Enlil was carried on and intensified between their sons, with brother sometimes turning against brother—a divine tale of Cain and Abel.

Some of these battles were against a deity identified as Kur—in all probability, Ishkur/Adad. This may well explain why Enlil deemed it advisable to grant his younger son a far-off domain, to keep him out of the dangerous battles for the succession.

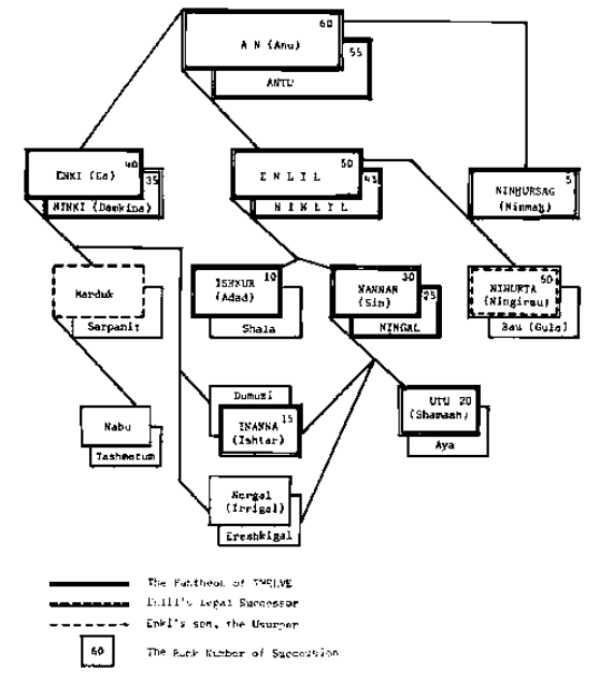

The position of the sons of Anu, Enlil, and Enki, and of their offspring, in the dynastic lineage emerges clearly through a unique Sumerian device: the allocation of numerical rank to certain gods.

The discovery of this system also brings out the membership in the Great Circle of Gods of Heaven and Earth when Sumerian civilization blossomed. We shall find that this Supreme Pantheon was made up of 12 deities.

The first hint that a cryptographic number system was applied to the Great Gods came with the discovery that the names of the gods Sin, Shamash, and Ishtar were sometimes substituted in the texts by the numbers 30, 20, and 15, respectively.

The highest unit of the Sumerian sexagesimal system—60—was assigned to Anu; Enlil “was” 50; Enki, 40; and Adad, 10.

The number 10 and its six multiples within the prime number 60 were thus assigned to male deities, and it would appear plausible that the numbers ending with 5 were assigned to the female deities.

Ninurta was assigned the number 50, like his father.

In other words, his dynastic rank was conveyed in a cryptographic message: If Enlil goes, you, Ninurta, step into his shoes. But until then, you are not one of the 12, for the rank of “50” is occupied.

Nor should we be surprised to learn that when Marduk usurped the Enlilship, he insisted that the gods bestow on him “the fifty names” to signify that the rank of “50” had become his.

There were many other gods in Sumer—children, grandchildren, nieces, and nephews of the Great Gods; there were also several hundred rank-and-file gods, called Anunnaki, who were assigned (one may say) “general duties.”

But only 12 made the Great Circle.

They, their family relationships, and, above all, the line of dynastic succession can better be referred to if we show them in a chart: