Refuting Zeno's Argument

Table of Contents

We shall not examine the validity of Zeno’s argument. Instead, we shall disclose his prejudices.

-

He supposes that bodies can be conceived to move so quickly that they cannot move more quickly.

-

He supposes time to be made up of moments, just as others have conceived quantity to be made up of indivisible points.

Both of these suppositions are false.

We are unable to think of a motion so fast that there is no motion faster.

The same holds true in the case of slowness. To conceive a motion so slow that there cannot be a slower, involves a contradiction.

This also applies to time, which is the measure of motion.

It is contrary to our intellect to conceive a timespan so short that there can be none shorter.

Let us suppose, with him, that a wheel ABC moves around its center at such a speed that point A is at every moment in position A.

I clearly conceive a speed indefinitely greater than this, and consequently moments that are infinitely less.

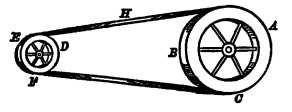

The wheel ABC moves around its center, with the help of a belt H it causes another wheel, DEF, half its size, to move about its center.

The wheel DEF is supposed to be half the size of the wheel ABC. The wheel DEF moves at twice the speed of the wheel ABC.

Consequently, point D is at every halfmoment again in the same place from which it began to move.

Then if we assign the motion of the wheel DEF to the wheel ABC, DEF will move 4 times faster than the original speed, and if we again assign this last speed of the wheel DEF to the wheel ABC, then DEF will move 8 times as fast, and so ad infinitum.

But this is quite clear merely from the concept of matter.

The essence of matter consists in extension, or ever-divisible space.

There is no motion without space.

One part of matter cannot occupy two spaces at the same time.

Therefore if a part of matter moves, it moves through some space.

This space is divisible no matter how small it is. Consequently, so is the time through which the motion is measured.

Consequently, the duration of that motion, or its time, is divisible, and is so to infinity. Q.E.D.

Zeno propounded another fallacious problem: If a body moves, it moves either in the place where it is, or in a place in which it is not.

But it cannot move in a place whgere it is because if it is in any place, then it must be at rest.

Nor can it move in a place where it is not.

Therefore, the body does not move.

But this line of argument is just like the previous one, for it also supposes that there is a time other than which there is no shorter.

If we reply that a body moves not in, but from, the place in which it is to a place in which it is not, he will ask whether it has not been in any intermediate places.

We reply by making a distinction: if by ‘has been’ he means ‘has rested’, we deny that it has been in any place while it was moving.

But if by ‘has been’ is understood ‘has existed’, we say that it has necessarily existed while it was moving.

He will again ask where it has existed while it was moving.

We may once more reply that if by ‘where it has existed’ he means ‘what place it has stayed in’ while it was moving, we say that it did not stay in any place.

But if he means ‘what place it has changed’.

We say that it has changed all those places that he may wish to assign as belonging to the space through which it was moving.

He will go on to ask whether at the same moment of time it could occupy and change its place.

We reply by making the following distinction: If by a moment of time he means a time other than which there can be none shorter, he is asking an unintelligible question.

Thus, it does not deserve a reply.

But if he takes time in the sense that I have explained previously (Le., its true sense), he can never assign a time so short that in it a body cannot occupy and change place, even though the time is supposed to be able to be shortened indefinitely.

This is obvious to one who pays sufficient attention.

Hence, he is supposing a time so short that there cannot be a shorter, and so he proves nothing.

Zeno has another argument in Descartes’s Letters Vol. 1, penultimate letter.

I have opposed Zeno’s reasoning with my own reasonings. I have refuted him by reason, not by the senses, as did Diogenes.

This is because the senses cannot produce for the seeker after truth anything other than the phenomena of Nature, by which he is determined to investigate their causes.

They can never show to be false what the intellect clearly and distinctly grasps as true.

This is the view we take, and so this is our method, to demonstrate our propositions with reasons clearly and distinctly perceived by the intellect, disregarding whatever the senses assert when that seems contrary to reason.

The senses can only determine the intellect to ask into one thing rather than another. They cannot convict the intellect of fulsity when it has clearly and distinctly perceived something.