Proposition 4 Problem 2

Table of Contents

Proposition 4 Problem 2

Supposing the force of gravity in any similar medium to be uniform, and to tend perpendicularly to the plane of the horizon ; to define the motion of a projectile therein, which suffers resistance proportional to its velocity.

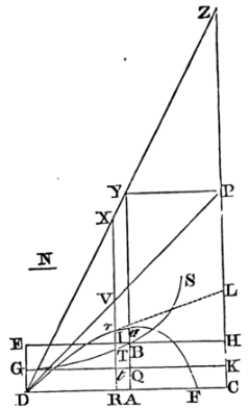

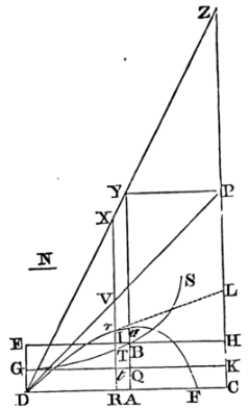

Let the projectile go from any place D in the direction of any right line DP, and let its velocity at the beginning of the motion be expounded by the length DP.

From the point P let fall the perpendicular PC on the horizontal line DC, and cut DC in A, so that DA may be to AC as the resistance of the medium arising from the motion upwards at the beginning to the force of gravity; or (which comes to the same) so that the rectangle under DA and DP may be to that under AC and CP as the whole resistance at the beginning of the motion to the force of gravity.

With the asymptotes DC, CP describe any hyperbola GTBS cutting the perpendiculars DG, AB in G and B; complete the parallelogram DGKC, and let its side GK cut AB in Q.

Take a line N in the same ratio to QB as DC is in to CP; and from any point R of the right line DC erect RT perpendicular to it, meeting the hyperbola in T, and the right lines EH, GK, DP in I, t, and V; in that perpendicular take Vr equal to tGT/N, or which is the same thing, take Rr equal to GTIE/N and the projectile in the time DRTG will arrive at the point r describing the curve line DraF, the locus of the point r; thence it will come to its greatest height a in the perpendicular AB; and afterwards ever approach to the asymptote PC.

Its velocity in any point r will be as the tangent rL to the curve. Q.E.I.

For N is to QB as DC to CP or DR to RV, and therefore RV is equal to

…

and Rr (that is, RV -Vr, or

…

is equal to

…

Let the time be expounded by the area RDGT and (by Laws, Cor. 2), distinguish the motion of the body into two others, one of ascent, the other lateral.

Since the resistance is as the motion, let that also be distinguished into two parts proportional and contrary to the parts of the motion: and therefore the length described by the lateral motion will be (by Prop. II, Book II) as the line DR, and the height (by Prop. III, Book II) as the area DR × AB - RDGT, that is, as the line Rr. But in the very beginning of the motion the area RDGT is equal to the rectangle DR × AQ.

Therefore that line Rr (or

will then be to DR as AB - AQ or QB to N, that is, as CP to DC;

Therefore as the motion upwards to the motion lengthwise at the beginning. Since, therefore, Rr is always as the height, and DR always as the length, and Rr is to DR at the beginning as the height to the length, it follows, that Rr is always to DR as the height to the length;

Therefore that the body will move in the line DraF, which is the locus of the point r. Q.E.D.

Cor. 1

Therefore Rr is equal to …

If RT is produced to X so that RX may be equal to …

that is, if the parallelogram ACPY be completed, and DY cutting CP in Z be drawn, and RT be produced till it meets DY in X; Xr will be equal to

and therefore proportional to the time.

Cor. 2.

Whence if innumerable lines CR, or, which is the same, innumerable lines ZX, be taken in a geometrical progression, there will be as many lines Xr in an arithmetical progression. And hence the curve DraF is easily delineated by the table of logarithms.

Cor. 3

If a parabola be constructed to the vertex D, and the diameter DG produced downwards, and its latus rectum is to 2 DP as the whole resistance at the beginning of the notion to the gravitating force, the velocity with which the body ought to go from the place D, in the direction of the right line DP, so as in an uniform resisting medium to describe the curve DraF, will be the same as that with which it ought to go from the same place D in the direction of the same right line DP, so as to describe a parabola in a non-resisting medium. For the latus rectum of this parabola, at the very beginning of the motion, is

…

and Vr is

…

But a right line, which, if drawn, would touch the hyperbola GTS in G, is parallel to DK, and therefore Tt is

…

N is

…

Therefore Vr is equal to

…

(because DR and DC, DV and DP are proportionals), to

…

and the latus rectum

…

comes out

…

that is (because QB and CK, DA, and AC are proportional),

…

and therefore ist to 2DP as DP

….

DA to CP

…

AC; that is, as the resistance to the gravity. Q.E.D.

Cor. 4

Hence if a body be projected from any place D in a right line DP with a speed.

The resistance of the medium, at the beginning of the motion, is given.

The curve DraF will be drawn.

The speed determines the latus rectum of the parabola.

Taking 2DP to that latus rectum, as the force of gravity to the resisting force, DP is also given. Then cutting DC in A, so that CP

AC may be to DP

DA in the same ratio of the gravity to the resistance, the point A will be given. And hence the curve DraF is also given.

Cor. 5

On the contrary, if the curve DraF be given, there will be given both the velocity of the body and the resistance of the medium in each of the places r. For the ratio of CP

AC to DP

DA being given, there is given both the resistance of the medium at the beginning of the motion, and the latus rectum of the parabola.

Tence the velocity at the beginning of the motion is given also. Then from the length of the tangent L there is given both the velocity proportional to it, and the resistance proportional to the velocity in any place r.

Cor. 6

But since the length 2DP is to the latus rectum of the parabola as the gravity to the resistance in D; and, from the velocity augmented, the resistance is augmented in the same ratio, but the latus rectum of the parabola is augmented in the duplicate of that ratio, it is plain that the length 2DP is augmented in that simple ratio only; and is therefore always proportional to the velocity; nor will it be augmented or diminished by the change of the angle CDP, unless the velocity be also changed.

Cor. 7

Hence appears the method of determining the curve DraF nearly from the phenomena, and thence collecting the resistance and velocity with which the body is projected. Let two similar and equal bodies be projected with the same velocity, from the place D, in different angles CDP, CDp.

Let the places F, f, where they fall upon the horizontal plane DC, be known. Then taking any length for DP or Dp suppose the resistance in D to be to the gravity in any ratio whatsoever, and let that ratio be expounded by any length SM. Then, by computation, from that assumed length DP, find the lengths DP, Df; and from the ratio

…

found by calculation, subduct the same ratio as found by experiment; and let the difference be expounded by the perpendicular MN.

Repeat the same a second and a third time, by assuming always a new ratio SM of the resistance to the gravity, and collecting a new difference MN.

Draw the affirmative differences on one side of the right line SM, and the negative on the other side; and through the points N, N, N, draw a regular curve NNN. cutting the right line SMMM in X, and SX will be the true ratio of the resistance to the gravity, which was to be found.

From this ratio the length DF is to be collected by calculation; and a length, which is to the assumed length DP as the length DF known by experiment to the length DF just now found, will be the true length DP. This being known, you will have both the curve line DraF which the body describes, and also the velocity and resistance of the body in each place.

SCHOLIUM

The resistance of bodies is in the ratio of the velocity, is more a mathematical hypothesis than a physical one. In mediums void of all tenacity, the resistances made to bodies are in the duplicate ratio of the velocities.

For by the action of a swifter body, a greater motion in proportion to a greater velocity is communicated to the same quantity of the medium in a less time;

In an equal time, by reason of a greater quantity of the disturbed medium, a motion is communicated in the duplicate ratio greater; and the resistance (by Law II and III) is as the motion communicated. Let us, therefore, see what motions arise from this law of resistance.