Scholium Continued

Table of Contents

Suppose an obstacle is interposed to hinder the congress of 2 bodies A, B, mutually attracting each other.

If either body, as A, is more attracted towards the other body B, than that other body B is towards the first body A, the obstacle will be more strongly urged by the pressure of the body A than by the pressure of the body B.

It will not remain in equilibrio.

The stronger pressure will prevail and will make the system of the 2 bodies, together with the obstacle, move directly towards B.

In free spaces, it willl go forward infinitely with a motion perpetually accelerated. This is absurd and contrary to the first Law.

By the first Law, the system should persevere:

- its state of rest, or

- moving uniformly forward in a right line

Therefore the bodies must equally press the obstacle, and be equally attracted one by the other. I made the experiment on the loadstone and iron. If these, placed apart in proper vessels, are made to float by one another in standing water, neither of them will propel the other; but, by being equally attracted, they will sustain each other’s pressure, and rest at last in an equilibrium.

So the gravitation betwixt the earth and its parts is mutual.

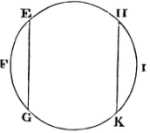

The earth FI is cut by any plane EG into 2 parts EGF and EGI. Their weights one towards the other will be mutually equal.

For if by another plane HK, parallel to the former EG, the greater part EGI is cut into two parts EGKH and HKI, whereof HKI is equal to the part EFG, first cut off, it is evident that the middle part EGKH, will have no propension by its proper weight towards either side, but will hang as it were, and rest in an equilibrium betwixt both.

But the one extreme part HKI will with its whole weight bear upon and press the middle part towards the other extreme part EGF; and therefore the force with which EGI, the sum of the parts HKI and EGKH, tends towards the third part EGF, is equal to the weight of the part HKI, that is, to the weight of the third part EGF. And therefore the weights of the two parts EGI and EGF, one towards the other, are equal, as I was to prove.

If those weights were not equal, the whole earth floating in the non-resisting aether would give way to the greater weight, and, retiring from it, would be carried off in infinitum.

And as those bodies are equipollent in the congress and reflexion, whose velocities are reciprocally as their innate forces, so in the use of mechanic instruments those agents are equipollent, and mutually sustain each the contrary pressure of the other, whose velocities, estimated according to the determination of the forces, are reciprocally as the forces.

So those weights are of equal force to move the arms of a balance; which during the play of the balance are reciprocally as their velocities upwards and downwards; that is, if the ascent or descent is direct, those weights are of equal force, which are reciprocally as the distances of the points at which they are suspended from the axis of the balance.

But if they are turned aside by the interposition of oblique planes, or other obstacles, and made to ascend or descend obliquely, those bodies will be equipollent, which are reciprocally as the heights of their ascent and descent taken according to the perpendicular; and that on account of the determination of gravity downwards.

And in like manner in the pully, or in a combination of pullies, the force of a hand drawing the rope directly, which is to the weight, whether ascending directly or obliquely, as the velocity of the perpendicular ascent of the weight to the velocity of the hand that draws the rope, will sustain the weight.

In clocks and such like instruments, made up from a combination of wheels, the contrary forces that promote and impede the motion of the wheels, if they are reciprocally as the velocities of the parts of the wheel on which they are impressed, will mutually sustain the one the other.

The force of the screw to press a body is to the force of the hand that turns the handles by which it is moved as the circular velocity of the handle in that part where it is impelled by the hand is to the progressive velocity of the screw towards the pressed body.

The forces by which the wedge presses or drives the two parts of the wood it cleaves are to the force of the mallet upon the wedge as the progress of the wedge in the direction of the force impressed upon it by the mallet is to the velocity with which the parts of the wood yield to the wedge, in the direction of lines perpendicular to the sides of the wedge.

The like account is to be given of all machines.

The power and use of machines consist only in this, that by diminishing the velocity we may augment the force, and the contrary: from whence in all sorts of proper machines, we have the solution of this problem.

To move a given weight with a given power, or with a given force to overcome any other given resistance. For if machines are so contrived that the velocities of the agent and resistant are reciprocally as their forces, the agent will just sustain the resistant, but with a greater disparity of velocity will overcome it.

So that if the disparity of velocities is so great as to overcome all that resistance which commonly arises either from the attrition of contiguous bodies as they slide by one another, or from the cohesion of continuous bodies that are to be separated, or from the weights of bodies to be raised, the excess of the force remaining, after all those resistances are overcome, will produce an acceleration of motion proportional thereto, as well in the parts of the machine as in the resisting body.

But to treat of mechanics is not my present business.

I was only willing to show by those examples the great extent and certainty of the third Law of motion. For if we estimate the action of the agent from its force and velocity conjunctly, and likewise the reaction of the impediment conjunctly from the velocities of its several parts, and from the forces of resistance arising from the attrition, cohesion, weight, and acceleration of those parts, the action and reaction in the use of all sorts of machines will be found always equal to one another. And so far as the action is propagated by the intervening instruments, and at last impressed upon the resisting body, the ultimate determination of the action will be always contrary to the determination of the reaction.