The Coalition Of Parties

Table of Contents

In a free government, the abolition of all distinctions of party may not be practicable, perhaps not desirable.

The only dangerous parties are those that aim to change the:

- essentials of government,

- succession of the crown, or

- considerable privileges of several members of the constitution

They prefer violence over compromise.

The parties in England had this animosity for over the last 100 years, which caused civil war sometimes. Recently, there have been the strongest universal desire to form a coaltion and abolish these party distinctions. This coalition can allow future happiness and should be cherished and promoted by every nationalist.

The best way towards coalition is to:

- prevent unreasonable insults and triumph of one party over the other,

- encourage moderate opinions,

- find the proper medium in all disputes,

- persuade each that its antagonist might be sometimes correct, and

- keep a balance in the praise and blame, which we bestow on either side.

I made my previous essays on the original contract and passive obedience for this purpose, to show that neither side is fully supported by reason.

I will prove that both parties:

- were justified by plausible topics

- meant well for the country

- had animosity based on narrow prejudice or vested interest

The popular Whig party use very specious arguments to oppose the crown. This opposition took place many reigns before Charles I. So they thought that there was no longer reason to submit to so dangerous an authority.

They reasoned that:

- the rights of mankind are forever sacred and cannot be abolished by any arbitrary power

- liberty is a blessing so inestimable that wherever it can be recovered, the people can willingly run many hazards, bloodshed, and spending for it

- all human institutions, especially the government, are in continual fluctuation.

- kings always want to rule. This is why universal despotism will prevail if the privileges of the people are not secured.

These views are surely large, generous, and noble. The kingdom owes its liberty, learning, industry, commerce, and naval power to their prevalence and success.

By them chiefly, the English name is distinguished among nations. It aspires to a rivalry with the freest and most illustrious commonwealths of antiquity.

These mighty consequences could not be foreseen when the contest began. This is why the royalists of the past did not want specious arguments to defend their prince.

They could have instead used the following arguments:

The only rule of government is use and practice. Reason is so uncertain a guide that it will always be exposed to doubt and controversy.

Could it ever render itself prevalent over the people, men had always retained it as their sole rule of conduct:

They had still continued in the primitive, unconnected, state of nature, without submitting to political government, whose sole basis is, not pure reason, but authority and precedent.

Dissolve these ties, you break all the bonds of civil society, and leave every man at liberty to consult his private interest, by those expedients, which his appetite, disguised under the appearance of reason, shall dictate to him.

The spirit of innovation is in itself pernicious, however favourable its goal might be.

A truth so obvious, that the popular party themselves are sensible of it; and therefore cover their encroachments on the crown by the plausible pretence of their recovering the ancient liberties of the people.

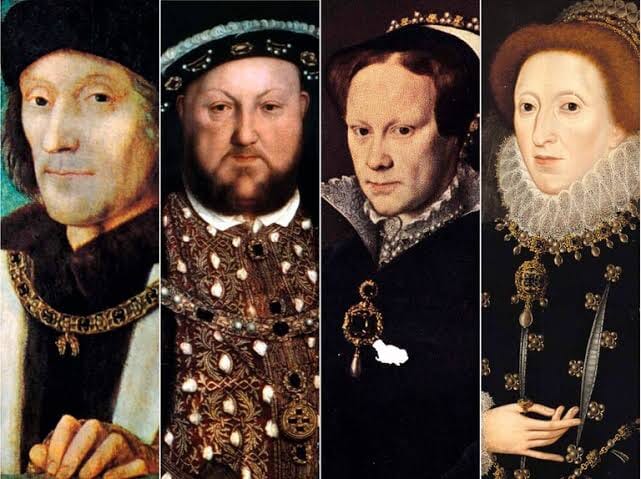

But the present prerogatives of the crown, allowing all the suppositions of that party, have been incontestably established ever since the accession of the House of Tudor; a period, which, as it now comprehends a hundred and sixty years, may be allowed sufficient to give stability to any constitution. Would it not have appeared ridiculous, in the reign of the Emperor Adrian, to have talked of the republican constitution as the rule of government; or to have supposed, that the former rights of the senate, and consuls, and tribunes were still subsisting?1

But the present claims of the English monarchs are much more favourable than those of the Roman emperors during that age.

The authority of Augustus was a plain usurpation, grounded only on military violence, and forms such an epoch in the Roman history.

But if Henry 7th really, as some pretend, enlarged the power of the crown, it was only by insensible acquisitions, which escaped the apprehension of the people, and have scarcely been remarked even by historians and politicians.

The new government is an imperceptible transition from the former. It is entirely engrafted on it and derives its title fully from that root.

The House of Tudor, and afterwards Stuart, exercised only the prerogatives claimed and exercised by the Plantagenets.

Their authority is not an innovation. The only difference is that the former kings exerted these powers only by intervals and not continuously because of the opposition of their barons.

Those ancient times were more turbulent and seditious that today. .

Why do the Whigs want to recover the ancient constitution?

The previous control over the kings was from the barons, not the commons.

The people had no authority nor liberty until the king:

- suppressed these factious tyrants,

- enforced the laws, and

- obliged everyone to respect each others rights, privileges, and properties.

The Whigs despise the king, so let them return to the ancient barbarous and feudal constitution. Let them be the retainers to a neighbouring baron and be his slave for his protection so that he can enslave his inferior slaves and villains.

This was the condition of the commons in the past. Back then, there was no magna carta. The barons themselves possessed few regular, stated privileges. The house of commons probably did not exist.

It is ridiculous to hear that the ancient commons usurped the power of government. The ancient representatives received wages from their constituents. But it was always considered a burden to be a member of the lower house. An exemption from it was considered as a privilege.

The Whigs say that the property acquired by the modern commons entitles them to more power than their ancestors enjoyed.

But I say that this encrease of their property is due to the encrease of their liberty and their security. The crown was restrained by the seditious barons in the past. The people in the past would have less liberty if the king had not dominated.

The true rule of government is the present established practice of the age. The most recent has most authority and also the best known.

Camden was the most copious, judicious, and exact of our historians. We would be entirely ignorant of the most important maxims of Elizabeth’s government without him.

The present monarchical government was:

- authorized by lawyers

- recommended by divines,

- acknowledged by politicians,

- passionately cherished by the people in general

All this happened in the last 160 years without the smallest murmur or controversy. This general consent, during so long a time, is enough to render a constitution legal and valid. If the origin of all power is derived from the people, as the Whigs suppose, then their consent is at its fullest here.

But I say that if government was created by the people’s consent, then they can also overthrow the government at their pleasure. This leads to instability by:

- exposing the crown to attack,

- puts the nobility in peril, followed by the gentry

The popular leaders will then assume the name of gentry and will next be exposed to danger. The people themselves will become incapable of civil government. For the sake of peace, they must admit a succession of military and despotic tyrants.

It is worse if the present fury of the people is incited by religious fanaticism, which is blind, headstrong, and ungovernable.

The event, if that can be admitted as a reason, has shown, that the arguments of the popular party were better founded; but perhaps, according to the established maxims of lawyers and politicians, the views of the royalists ought, before-hand, to have appeared more solid, more safe, and more legal.

The more moderate we represent those past events, the closer we can have a coalition of the parties.

Moderation is of advantage to every establishment. Only zeal can overturn a settled power. An over-active zeal in friends is apt to beget a like spirit in antagonists.

The transition from a moderate opposition against an establishment, to an entire acquiescence in it, is easy and insensible.

There are many invincible arguments, which should induce the malcontent party to acquiesce entirely in the present settlement of the constitution.

They now find, that the spirit of civil liberty, though at first connected with religious fanaticism, could purge itself from that pollution, and appear under a more genuine and engaging aspect; a friend to toleration, and an encourager of all the enlarged and generous sentiments that do honour to human nature.

The popular claims could stop at a proper period. After retrenching the high claims of prerogative, could still maintain a due respect to monarchy, to nobility, and to all ancient institutions.

The very foundation of their party is liberty. It gave the party its chief authority, but has now deserted them and gone over to their antagonists.

The plan of liberty is settled; its happy effects are proved by experience; a long tract of time has given it stability;

Whoever tries to overturn it to recall the past government or abdicated family, would, besides other more criminal imputations, be exposed, in their turn, to the reproach of faction and innovation.

While they peruse the history of past events, they should reflect, both that those rights of the crown are long since annihilated, and that the tyranny, and violence, and oppression, to which they often gave rise, are ills, from which the established liberty of the constitution has now at last happily protected the people.

These reflections will prove a better security to our freedom and privileges, than to deny, contrary to the clearest evidence of facts, that such regal powers ever had an existence. There is not a more effectual method of betraying a cause, than to lay the stress of the argument on a wrong place, and by disputing an untenable post, enure the adversaries to success and victory.