Politics May Be Reduced To a Science

Table of Contents

It is wrong to say that all governments are alike, and that their only difference is in the character and conduct of the governors. If this were true, then most political disputes would end and there would be just one constitution for all.

I condemn the idea that human affairs are merely caused by the casual humours and characters of particular men.

The goodness of all government is in the goodness of the administration.

Compare the French government under Henry III and Henry IV.

- Henry 3rd’s reign had oppression, levity, and artifice in its rulers, and faction, sedition, treachery, rebellion, disloyalty in its subjects.

- Henry 4th was a patriot and heroic prince who succeeded Henry III. He caused everything to totally change.

The difference was caused by the difference in the temper and conduct of these two sovereigns. Instances of this kind may be multiplied, almost without number, from ancient as well as modern history, foreign as well as domestic.

All absolute governments depend very much on the administration. This is one of the great inconveniences of absolutism.

But a republican and free government would be absurd if the checks and balances, from the constitution:

- were impotent, and

- made no one, even bad men, to act for the public good.

Governments would be the source of all disorder and of the blackest crimes if skill or honesty were lacking in their original frame and institution.

The force of laws and forms of government are so great. They depend so little on the humours and tempers of men, that both general and specific consequences can be deduced from them sometimes, just like any mathematical formula.

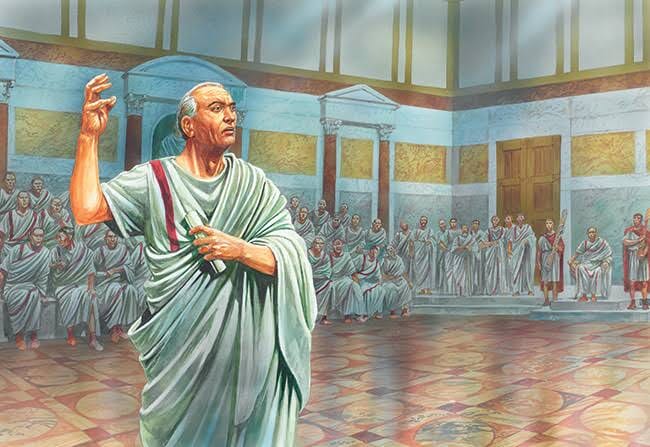

The Roman republic’s constitution gave the whole legislative power to the people, without giving veto power to the nobility or consuls. This unbounded power was in a collective, not in a representative body.

Conquest enlarged the republic’s population size which was spread far from the capital. This caused the votes to be won by the contemptible city-tribes.

Those urban people supported policies that gave them grains and bribes, making them more licentious everyday. The Campus Martius became a perpetual scene of tumult and sedition.

Armed slaves were introduced among these rascally citizens. This caused them to fall into anarchy and forced the Romans into the despotic power of the Caesars.

Such are the effects of democracy without a representative.

A Nobility may possess the legislative power of a state in two ways:

- Every nobleman shares the power with the whole body

An example is the Venetian aristocracy. In it, the nobility has the whole power. No nobleman has any authority which he receives not from the whole.

- The whole body enjoys power in parts, each having a distinct power and authority.

An example is the Polish government where every nobleman has a distinct hereditary authority over his vassals through his fiefs, the concurrence of which gives the authority to the whole.

The Venetian system is better because it avoids the instability of individual interests and education of the Polish system.

A nobility, who possess their power in common, will preserve peace and order, among themselves and their subjects.

No noble can have enough power to control the laws for a moment.

The nobles will preserve their authority over the people, but without any grievous tyranny, or any breach of private property. This is because it would not be the interest of the whole body, however it may be for some individuals.

The only distinction in the state will be a distinction of rank between the nobility and people. The whole nobility will form one body, and the whole people another, without the usual private feuds. This shows the disadvantages of a Polish nobility.

A free government can have a single prince or king holding a large share of power in order to balance the other parts of the legislature. This chief magistrate may be elected or be hereditary. The hereditary way leads to more inconveniencies than the elective way. This election will to divide the whole people into factions. Upon every vacancy, a civil war will likely happen.

The prince elected must be either:

a Foreigner

He:

- is ignorant of the people he is to govern

- is suspicious of his new subjects and suspected by them

- prefers foreigners. These only care about enriching themselves in the quickest manner, while their master’s favour and authority are able to support them.

a Native

He:

- will carry his old private animosities and friendships with him.

- will excite the envy of those who formerly considered him as their equal

A crown is too much of a reward to be given to merit alone. It will always induce the candidates to employ force, money, or intrigue, to procure the votes of the electors. In this way, the election will just be the same as when the position was hereditary.

It may therefore be pronounced as an universal axiom in politics, That an hereditary prince, a nobility without vassals, and a people voting by their representatives, form the best monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy.

Maxim: Free governments are commonly the most happy for those who have freedom. But they are the most ruinous and oppressive to their provinces.

When a monarch conquers new lands, he soon learns to treat his old and his new subjects as equals. He makes the general laws apply to them equally.

But a free state necessarily makes a great distinction until the citizens learn to love their neighbours as themselves.

In such a government, the conquerors are also lawmakers. They will contrive matters as to draw some private and public advantage from their conquests:

- by restrictions on trade, and

- by taxes

Provincial governors have also a better chance, in a republic, to escape with their plunder, by means of bribery or intrigue; and their fellow-citizens, who find their own state to be enriched by the spoils of the subject provinces, will be the more inclined to tolerate such abuses.

A free state changes its governors frequently as a precaution. This obliges these temporary tyrants to be more expeditious and rapacious so that they may accumulate wealth before they are replaced.

The Romans had laws to prevent the oppression by their provincial governors. But Cicero tells us that the Romans repealed these very laws for the sake of those provinces.

- When the laws were in place, the tyrants would plunder to satisfy themselves, as well as the judges and the great men in Rome who protected those governors.

- Without those laws, those governors would plunder only for themselves

Cicero had exhausted all the thunders of his eloquence against Gaius Verres, a corrupt governor, in order to have him exiled. Yet that cruel tyrant lived to old age, in opulence and ease. Thirty years later, he was put into the proscription by Mark Anthony because of his exorbitant wealth.

Tacitus tells us that after the republic’s dissolution, the Roman yoke became easier on the provinces. Many of the worst emperors, such as Domitian, were careful to prevent all oppression on the provinces.

Polybius tells us that the oppression and tyranny of the Carthaginians over their subject states in Africa was so severe. They were not content with exacting half of all the produce of the land, but also loaded them with many other taxes.

This is true even in modern times. The provinces of absolute monarchies are always better treated than those of free states.

This is seen in:

- the difference between the Païs conquis of France and Ireland.

- the Persians, under the Greeks of Alexander, not making the smallest effort to recover their former independence, as observed by Machiaveli.

According to Machiaveli, the cause is that a monarch may govern his subjects in two ways:

- He may rule absolutely, like the eastern princes

He can stretch his authority so far as to leave no distinction of rank among his subjects. There are:

- no advantages of birth,

- no hereditary honours and possessions and

- no credit among the people, except from his commission alone.

After a conquest, it is impossible ever to shake off the yoke since no one has so much personal credit and authority to lead the people.

- He may exert his power more mildly, like other European princes

He can leave other sources of honour: Birth, titles, possessions, valour, integrity, knowledge, or great achievements.

The least discord among the conquerors will encourage the people to rebel since they already have leaders ready to guide them.

This seems solid and conclusive. Machiaveli, however, added a fallacy that monarchies following the eastern policy are the most difficult to subdue, though are more easily kept when once subdued. This cannot happen because:

- a tyrannical government weakens the courage of men and makes them indifferent on the fortunes of their sovereign

- the temporary and delegated authority of their generals and magistrates are also absolute which then leads to the most dangerous and fatal revolutions

This is why a gentle government is preferable, and gives the greatest security to the sovereign and his subjects.

Legislators, therefore, should not trust the future government of a state entirely to chance. They should provide a system of laws to regulate the administration of public affairs to posterity.

In the smallest court or office, the stated forms and methods, by which business must be conducted, are a considerable check on mankind’s natural depravity.

The same can be done for the public affairs. The stability and wisdom of the Venetian government is due to its form of government.

It is easy to point out the defects in the original constitutions of Athens and Rome which produced their tumultuous governments and led to their ruin.

The rise and fall of governments depend so little on the humours and education of particular men. One part of the same republic may be governed well, while another is unstable, by the very same men because of the differences in the institutions of those parts.

This was actually the case with Genoa. It was always full of sedition, tumult, and disorder, while the bank of St. George, a big part of the state, was conducted with the utmost integrity and wisdom for several ages.

The ages of greatest public spirit are not always most eminent for private virtue. Good laws may beget order and moderation in the government while the people’s manners and customs have little humanity or justice.

The best political periods of Roman history was that between the beginning of the first Punic war, and the end of the last Punic war. Back then, the balance between the nobility and the people were fixed by the contests of the tribunes and not by the extent of conquests.

It was then that the horrid practice of poisoning was so common. A Praetor gave capital punishment to over 3,000 persons in a part of Italy for this crime.

They were really more virtuous during the time of the two Triumvirates when they were:

- tearing their common country to pieces, and

- spreading slaughter and desolation merely for the choice of tyrants.

In every free state, we should maintain with utmost zeal those institutions which:

- secure liberty

- consult the public good, and

- restrain and punish the avarice or ambition of particular men.

Zealots on both sides who kindle up the passions of their partizans. Under pretence of public good, they pursue the interests and ends of their particular faction.

I always promote moderation than zeal. The surest way of producing moderation in every party is to increase our zeal for the public.

Let us try to be moderate with regard to the parties that currently divide our country. At the same time, we should not let this moderation reduce our industry and passion for the good of the country.

Those who either attack or defend a minister in our free government always

- carry matters to an extreme, and

- exaggerate his merit or demerit with regard to the public.

His enemies charge him with the greatest crimes, both in domestic and foreign management:

- unnecessary wars,

- scandalous treaties,

- profusion of public treasure,

- oppressive taxes,

- every kind of mal-administration

To aggravate the charge, they say that his pernicious conduct will extend its baleful influence even to posterity by:

- undermining the best constitution in the world, and

- disordering that wise system of laws, institutions, and customs which have happily governed our ancestors so many centuries.

On the other hand, the minister’s partizans make his panegyric run as high as those accusations. They celebrate his wise, steady, and moderate conduct of his administration:

- the nation’s honour and interest abroad,

- the public credit maintained at home,

- the persecutions restrained and faction subdued.

The merit of all these blessings is ascribed solely to the minister. At the same time, he crowns all his other merits by a religious care of the best constitution in the world, which he has preserved and transmitted entire to the future generations.

The attack and defense from the partizans of each party:

- beget an extraordinary ferment on both sides, and

- fill the nation with violent animosities.

Both the attackers and defeners fail the see their contradictions.

To the attackers:

If our constitution were really that excellent, then it would never have created a wicked and weak minister to govern triumphantly for 20 years when opposed by the greatest geniuses in the nation who used the freedom of expression in parliament and in public. If the minister is wicked and weak, then it means that the constitution is faulty in its original principles. A good constitution should have provided a remedy against mal-administration.

To the defenders:

If our constitution is so excellent then a change of ministry cannot be a dreadful event since it is essential to our constitution.

If our constitution is very bad then such a jealousy and apprehension on the changes is ill-placed. We should expect changes in ministers just as a husband who had married a woman from a bar should expect her infidelity. Public affairs, in such a government, must necessarily go to confusion anyway. The zeal of patriots is in that case is less needed than the patience and submission of philosophers. The virtue and good intentions of Cato and Brutus are highly laudable. But, to what purpose did their zeal serve? They only hastened the decline of the Roman government and rendered its convulsions and dying agonies more violent and painful. In such a case, the claims of moderate men should be examined or admitted.

The country-party might still assert, that our constitution still allows mal-administration even if it is excellent. Therefore, if the minister is bad, it is proper to oppose him with some zeal.

On the other hand, the court-party may be allowed to defend the minister, with some zeal too, if he were good.

In this case, the people should not change a good constitution into a bad one, by the violence of their factions.

The best civil constitution is one that restrains every man by the most rigid laws. In it, it is easy to discover the intentions of a minister, and to judge, whether his personal character deserve love or hatred.