Superphysics

A New Science Based on Waves, Socratic Dialectics, and Cartesian Physics for Solving Problems.

Natural science is divided into physic and metaphysic. Physic should contemplate that which is inherent in matter and therefore transitory. Metaphysic should contemplate that which is abstracted and fixed.

All Knowledge Can Be Grouped Into Three

Metaphysics

1-50% Replicable: Paradoxical

Superphysics

51-99% Replicable: Subjective

Physics

100% Replicable: Objective

There are 3 principal sciences: Mechanics, Medicine, Ethics

Six Sciences That Open Up The Universe

Material Superphysics

Replacing the Physics of Newton and Einstein with that of Descartes and Spinoza

Bio Superphysics

Biology and Medicine that combines Western and Asian Principles

Social Superphysics

A Society as a Metaphysical Organism with a Life Cycle

Spiritual Superphysics

Upgrading Experience beyond Matter and into the Aether or Akasha

Supermath and Qualimath

Mathematics based on Base-3, Base-6, Shapes, and Qualities

Superlogic

Reasoning based on Dharma or True Nature

Things cannot have absolute Existence without any relation to their being perceived. They cannot have any Existence without the Minds which perceive them. I find it strange that people think that Houses, Mountains, and all sensible Objects have a Real Existence, distinct from their being perceived by the Understanding.

Let's Solve All Problems!

Evidence

We test Superphysics in the real world

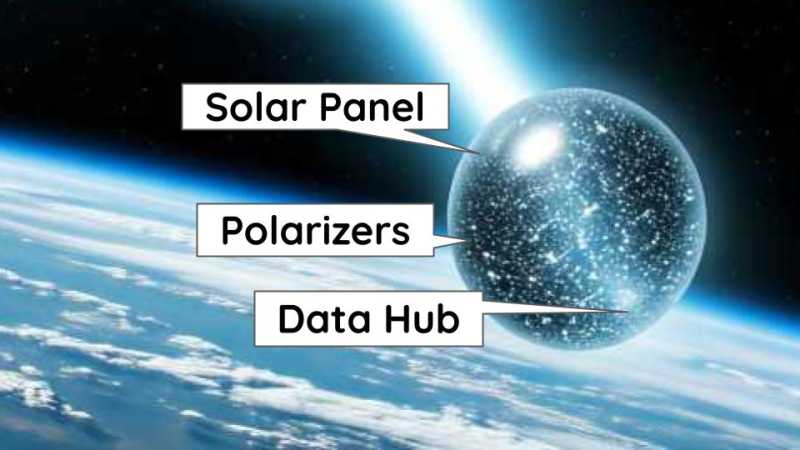

Proposed Solutions and Technologies

Enlightenment ideas can lead to totally new technologies

Predictions from Social Cycles

We test our predictions with actual events

Policies from Social Cycles

A better world needs policies that match Nature

Stay Updated

Join our newsletter for updates.