The 4 Basic Operations

Table of Contents

To this end, only 4 operations are required: addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division.

The last two are often not to be completed here, both so that nothing is rashly involved and so that they can be completed more easily later.

The multitude of rules often comes from the ignorance of the teacher.

Those rules which could be reduced to one single general precept, are less obvious if they are divided into many particularities.

Therefore, here we have reduced all the operations, by which we should use in resolving questions, that is, in deriving certain magnitudes from others, to only four heads; and how sufficient they are will be known from their explanation.

Namely, if we arrive at the knowledge of a single magnitude, from the fact that we have parts from which it is composed, this is done through addition;

if we recognize a part from the fact that we have a whole, and the excess of the whole above the same part, this is done through subtraction;

no magnitude can be deduced from others absolutely taken in more ways, and in which in some way it is contained.

But if it must be found from others by which it is distinctly different, and in which in no way it is contained, it is necessary that it be compared to them by some reason;

This relation or habit, if it is directly pursued, then multiplication must be used; if indirectly, division.

Which 2 so that they may be clearly exposed, it must be known that the unity, of which we have now spoken, here is the basis and the foundation of all the relations, and it in the series of continuously proportional magnitudes obtains the first degree, but the given magnitudes contain in the second degree, and in the third, fourth, and the rest of the inquest, if the proportion is direct; if indeed indirect, the inquest is contained in the second and other intermediate degrees, and the data in the last.

If a unit to a, or to 5 the given, so b either 7 the data to be sought, which is from a to 35, then a and b are in the second degree, and ab, which arises from these, in the third. Likewise, if it be added that, as a unit to c either 9, so to ab either 35 the data to be sought, which is the abc or 315, then the abc is in the fourth degree, and is generated through two multiplications from ab and c, which are in the second degree, and so forth with the others.

Likewise, as a unit to a (or 5), so a (or 5) to a^2 (or 25).

As a unit to a (or 5), so a^2 (or 25) to a^3 (or 125)

As a unit to a (or 5), thus a^3 (or 125) to a^4, which is 625, etc.

Neither otherwise is multiplication made, if the same magnitude is conducted by itself, as if by another quite different.

If as a unit to a (or 5) datum divisor, so B or 7 sought to be found or B or 35 the given to be divided, then the order is confused and indirect: why indeed, B sought is not taken, unless by dividing the B data by a and also the data.

Likewise, if as a unit to A or 5, so A or 5 the sought, so A or 5 to a2 or 25 the given, or, as a unit to A

All this we cover under the name of division, which is more difficult than the former since in them is often found the sought magnitude, which therefore involves many relations.

These examples of the same sense, as if it were said to extract the square root of a2 or from 25, or cubic from a3 or 125, and so forth, are customarily spoken among the logicians.

Or, even to explain those of the geometrists, it is the same as if it were said to find the mean proportional between that size that we took, which is the unit, and that by a2, or by two mediums, between the unit and a3, and so forth with others.

From which, it is easily collected, in what way these two operations are sufficient to discover whatever magnitudes, which are for some relation from others.

Addition or subtraction is done by conceiving a line, or as the idea of an extended magnitude in which length alone is to be regarded.

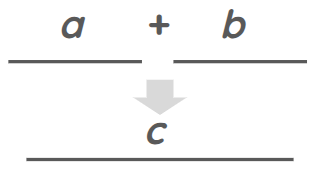

If a line is to be added from a to line b, one is joined to the other in this way ab, producing c.

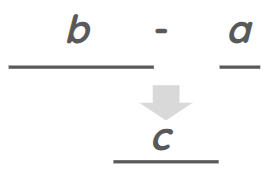

But if the lesser is taken from the greater, as b from a, one is applied to the other in this way:

And so it holds that part of the greater which cannot be covered by the lesser, namely, c.

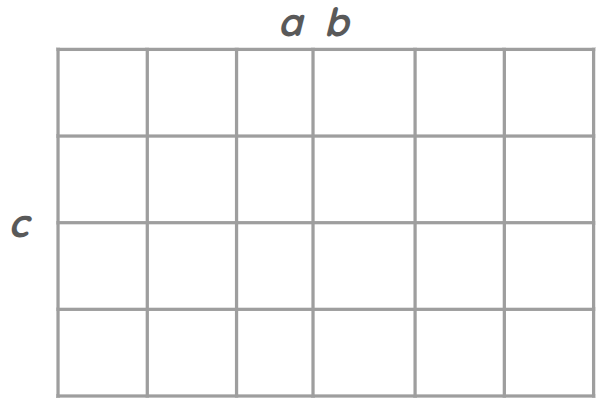

In multiplication, we conceive even the given magnitudes under the idea of lines.

But we imagine them to make a rectangle. If we multiply a by b, one is applied to the other in this way at right angles, and it is a rectangle.

If we wish to multiply ab by c, we should conceive ab as a line ab, so that abc is done for:

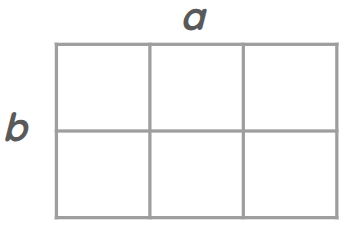

Finally, in the division, in which the divisor is given, we imagine the magnitude to be divided as a rectangle, one side of which is a divisor, and another is a quotient.

If Rectangle ab is divided by a then:

- the width is taken away from it

- the b remains, for the quotient

Conversely, if the same is to be divided by b, then:

- the height is taken from b

- the quotient will be a

In these divisions, however, in which the divisor is not given, but only in some way designated by any relation, as when it is said that the square root, or the cube is to be extracted, etc., then it is to be noticed that the term is to be divided and all others are always to be conceived as existing in the order of the series of proportions, of which the first is unity and the last is the magnitude to be divided.