The Nature of the Earth's interior

Table of Contents

57. The nature of the Earth’s interior

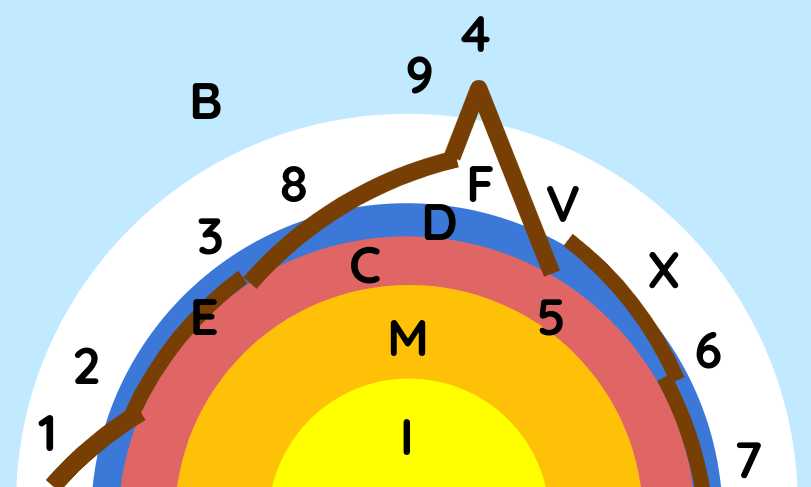

The interior of body C consists of particles of any shape.

They are so dense that the air-aether globules, in their ordinary motion, do not carry them away but only make them heavy by pressing downward.

These particles are moved somewhat by passing through the numerous channels found among them.

This is also done by:

- the fire-aether, filling those narrow channels

- the earth-aether particles of the upper bodies

DandE- These often descend into the widest of them and thus carry away some of the dense particles of this body.

The upper surface consists of branching parts firmly connected to each other.

- These parts sustained and broke the impact of the air-aether globules flowing through bodies

BandDduring the formation of this body.

Nonetheless, many relatively wide intervals exist.

- This allows particles of fresh water, salt, and other angular or branched particles from body E to pass through them.

58. The nature of quicksilver

Beneath this surface, the parts of body C adhere less tightly to each other, and perhaps at a certain distance from it.

They:

- press on each other due to their gravity

- do not allow the air-aether globules to flow around them from all sides

Yet many of them are congregated with shapes so round and smooth.

- This makes them easily agitated.

This agitation is caused both by the finer air-aether globules among them.

- These find some spaces between them, especially those left by the fire-aether filling all the narrow angles left there.

Consequently, they form a very dense and least transparent liquid, called quicksilver.

59. The inequality of the heat permeating the Earth’s interior

We see the spots generated daily around the Sun having very irregular and diverse shapes.

The central region M of the Earth is composed of similar matter to these spots.

These are not uniformly dense everywhere. And so, they provide passage for more of the fire-aether in some places than in others.

The fire-aether passing through body C moves its parts more strongly in some places than in others.

Similarly, the heat excited by the Sun’s rays reaching the depths of the Earth does not act uniformly on this body C.

This is because it communicates more easily through fragments of body E than through water D.

Also, the height of mountains causes some parts of the Earth, facing the Sun, to become much hotter than those facing away from it.

They also heat differently toward the Equator and the poles. This heat varies periodically due to the alternation of day and night and especially summer and winter.

60. The action of this heat

As a result, all the particles of this Earth’s interior C always move somewhat.

This applies not only to those not closely connected but also to the hardest ones that adhere very firmly to each other.

These dense and branching particles of body C are connected and intertwined in such a way that they do not tend to separate entirely due to the force of heat.

Instead, they are shaken somewhat and open the channels around them more or less.

Some particles are harder than others, having fallen from the upper bodies D and E into these channels. They easily crush and break them with their motion.

Consequently, they reduce them to 2 kinds of shapes.

61. Sharp and acidic juices, from which ink, vitriol, alum, etc., are made.

Particles with a slightly more solid material, such as salt, intercepted and crushed in these channels, become flat, rigid, and flexible from round and rigid shapes.

This is similar to how the round rod of glowing iron can be flattened into an oblong plate by frequent blows from hammers.

Meanwhile, these particles, driven by the force of heat, crawl through these channels and, adhering and rubbing against their hard walls, become sharpened like the tips of swords. Thus, they turn into sharp, acidic, and erosive juices.

When these juices later solidify with metallic matter, it becomes ink; with stone, it becomes vitriol; and so on for many other substances.

62. The oily matter of bitumen, sulfur, etc.

Many softer particles have fallen from the external earth E, as well as those of fresh water thoroughly filtered there.

- These become so thin that they are torn apart by the motion of the fire-aether.

- They are divided into numerous extremely fine and flexible branches.

These branches adhere to other terrestrial particles and make up+-+ sulfur, bitumen, and all other fatty or oily substances found in mines.

63. The principles of alchemists and how metals ascend into mines

These 3 are the commonly accepted principles of alchemists:

- Taking sharp juice for salt

- The softest branches of oily matter for sulfur

- Quicksilver itself for their mercury.

All metals come to us only because sharp juices, flowing through channels of body C, separate some of its particles.

These particles are later enveloped and clothed in oily matter. This makes them easily carried upward by quicksilver when it is decompressed by heat.

They form various metals according to their different magnitudes and shapes.