The Microscope

Table of Contents

Nature has not given us the means of looking at objects more closely than around 1 foot or half a foot away.

To add to it, we can interpose a glass such as that which is marked P[30].

This will cause only the 12th or 15th part of as much space between the eye and the object as there was without it.

This will affect the rays which come from this object, crossing 12 or 15 times nearer to it because the light will no longer cross on the eye’s surface.

Instead, the light will cross on the surface of the glass to which the object will be closer.

They will form an image whose diameter will be 12 or 15 times greater than it could be if one did not use this glass.

Consequently its surface will be about 200 times larger.

If, looking at the object X through the glass P, we position our eye C in the same way as it should be to see another object which would be twenty or thirty paces from it, and that, having no knowledge of the place where this object X is, we judge it to be really thirty paces away, it will seem more than a million times larger than it is, so that it can become from a flea an elephant; for it is certain that the image which a flea forms at the back of the eye, when it is so close to it, is no less great than that which an elephant forms there when it is thirty paces away. And it is on this alone that the whole invention of these little smart glasses is based, composed of a single lens, the use of which is quite common everywhere, although the true figure has not yet been known. they must have: and, because we usually know that the object is very close when we use them to look at it, it cannot appear so large as it would if we imagined it further away.

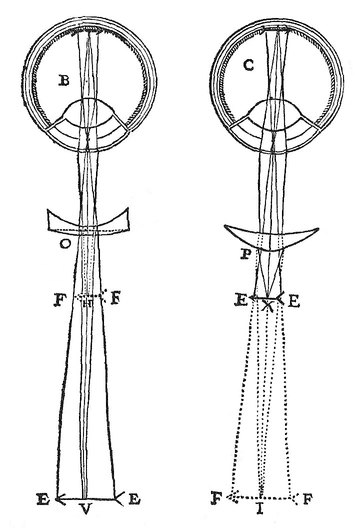

There remains only one other means of increasing the size of the images, which is to cause the rays which come from various points of the object to cross as far as possible from the fundus of the eye; but it is without comparison the most important and the most considerable of all, because it is the only one that can serve for inaccessible objects as well as for accessible ones and whose effect has no limits: so that one can, by using it, increase the images more and more up to an indefinite size: as, for example, as much as the first of the three liquors with which the eye is filled causes almost the same refraction than common water, if we apply everything against a pipe full of water, like EF[31], at the end of which there is a GHI glass, whose shape is very similar to that of the BCD skin which covers this liquor , and even relates to the distance from the bottom of the eye, there will no longer be any refraction at the entrance to this eye; but that which was done there before, and which was the cause that all the rays which came from the same point of the object began to bend from that place to go and assemble at the same point on the extremities of the object. optic nerve, and that then all those which came from various points cross there to go to return on various points of this nerve, will be done as of the entry of the tube GI; so that these rays, crossing from there, will form the image RST much larger than if they crossed only on the surface BCD, and they will form it larger and larger, according as this pipe is longer. And thus the water EF doing the office of the humor K, the glass GHI that of the skin BCD, and the entrance of the pipe GI that of the pupil, the vision will take place in the same way as if nature had made the eye longer than it is the whole length of this pipe, without there being anything else to notice, except that the real pupil will then be not only useless, but even harmful, in that it will exclude by its smallness the rays which could go towards the sides of the fundus of the eye, and thus prevent the images from extending there in as much space as they would if it were not so narrow. I must also not forget to warn you that the particular refractions, which take place a little differently in GHI glass than in EF water, are not considerable here, because this glass being everywhere equally thick. , if the first of its surfaces makes the rays bend a little more than would that of water, the second straightens them as much at the same time; and it is for this same reason that above I have not spoken of the refractions which the skins which envelop the humors of the eye can cause, but only of those of its humors.

Now, all the more so since it would be very inconvenient to join water against our eye in the way that I have just explained, and even since, not being able to know precisely what is the shape of the BCD skin which covers it, we cannot determine exactly that of the GHI glass to substitute it in its place; it will be better to make use of another invention, and to make, by means of one or more glasses, or other transparent bodies also enclosed in a tube, but not joined to the eye so exactly as to only a little air remains in between, that, as soon as this pipe enters, the rays which come from the same point of the object bend or bend in the way that is required, to make that they go to gather in another point towards the place where the middle of the bottom of the eye will be when this pipe is put in front. Then, once again, let these same rays, on leaving this pipe, bend and straighten up in such a way that they can enter the eye just as if they had not been bent at all, but only that they came from some nearer place; and then that those who will come from various points, having crossed at the entrance of this pipe, do not uncross at the exit, but that they go towards the eye in the same way as if they came from a object that was larger or closer.

As if the pipe HF[32] is filled with an entirely solid glass whose surface GHI is of such figure that it causes all the rays which come from the point X, being in the glass, to tend towards S; and that its other surface KM folds them again in such a way that they tend from there towards the eye in the same way as if they came from the point x, which I suppose in such a place that the lines xC and CS have between themselves proportion than XH and HS; those coming from point V will necessarily cross them in the area GHI, so that, being already far from them, when they are at the other end of the pipe, the area KM will not be able to bring them closer, mainly if it is concave, as I suppose, but it will send them back towards the eye in much the same way as if they came from the point v, by means of which they will form the RST image all the larger as the hose will be longer; and it will not be necessary, in order to determine the figures of the transparent bodies which one will want to use for this purpose, to know exactly what is that of the surface BCD.

But, for what it would once again be inconvenient to find glasses or other such bodies which were thick enough to fill the entire HF pipe, and clear and transparent enough not to prevent the passage of light , we can leave empty the whole inside of this pipe and put only two glasses at its two ends, which have the same effect as I have just said that the two surfaces GHI and KLM should have. And it is on this alone that the whole invention of these glasses is based, composed of two lenses placed at the two ends of a pipe, which gave me the opportunity to write this treatise.

The third condition for perfect sight is that the light which moves each thread of the optic nerve should not be too strong nor too weak.

This is facilitated by our pupils the ability to shrink and widen

Sometimes, the light is too strong for our pupils, such as when we look at the sun. This is remedied by:

- placing against the eye some black body with a very narrow hole to act as the pupil or

- looking through a crape or some other such somewhat obscure body, and which only lets into the eye as many rays from each part of the object as are needed to move the optic nerve without injuring it.

When the light is too weak, we can make them stronger with the help of a mirror or glass.

Then, besides that, when one uses the glasses of which we have just spoken, especially since they make the pupils useless, and it is the opening through which they receive the light from outside that does its job, it is also this that we must enlarge or shrink, depending on whether we want to make the vision stronger or weaker.

If we did not make this opening wider than the pupil is, the rays would act less strongly against each part of the fundus of the eye than if we did not use spectacles: and this in same proportion as the images which would be formed there would be larger, without counting what the surfaces of the interposed glasses deprive of their force. But it can be made much wider, and this all the more so as the glass which straightens the rays is situated nearer to the point towards which the one who bent them made them tend.

As if the GHI glass causes all the rays that come from the point we want to look at to tend towards S[33], and that they are straightened by the KLM glass, so that from there they tend parallel towards the eye: to find the greatest width that the opening of the pipe can have, it is necessary to make the distance which is between the points K and M equal to the diameter of the pupil; then, drawing from the point S two straight lines which pass through K and M, namely SK, which must be extended as far as g, and SM as far as i, we will have gi for the diameter which we are looking for: for it is manifest that, if it were made larger, there would not therefore enter into the eye more rays from the point towards which one raises one’s sight, and that, for those who would come there from other places, not being able to help to the vision, they would only make it more confused.

Diopter figure 31.jpg

But if, instead of the KLM glass, we use klm, which, because of its shape, must be placed closer to the point S, we will once again take the distance between the points k and m equal to the diameter of the pupil; then, drawing the straight lines SkG and SmI, we will have GI for the diameter of the opening sought, which, as you see, is greater than gi in the same proportion as the line SL surpasses Sl.

And if this line Sl is not greater than the diameter of the eye, the vision will be nearly as strong and as clear as if one did not use glasses, and if the objects were as a reward closer than they are not, especially as they appear larger: so that, if the length of the pipe causes, for example, the image of an object thirty leagues away to form as large in the eye as if it were only thirty paces distant, the width of its entrance, being such as I have just determined it, will cause this object to be seen as clearly as if, being really only thirty paces distant from it, one looked at him without glasses. And if we can make this distance between the points S and l even less, the vision will be even clearer.

But this is mainly only useful for inaccessible objects; because, for those who are accessible, the opening of the pipe can be all the more narrow as one approaches them more, without for that that the vision of it is less clear; as you can see that no less rays from the point X[34] enter the small glass gi than the large GI; and finally it cannot be wider than the glasses that are applied to it, which, because of their shapes, must not exceed a certain size, which I will determine below.

That if sometimes the light which comes from objects is too strong, it will be very easy to weaken it by covering all around the extremities of the glass which is at the entrance to the pipe, which will be better than putting a few others in front glasses more cloudy or colored, as many are wont to do to look at the sun: because, the more this entrance will be narrow, the more the vision will be distinct, as it was said above of the pupil. And it must even be observed that it will be better to cover the glass from the outside than from the inside, so that the reflections which may be made on the edges of its surface do not send any rays towards the eye; for these rays, not serving the vision, could harm it.

There is now only one condition which is desired on the part of the external organs, which is to make one perceive as many objects as possible at the same time; and it is to be observed that it is in no way required for perfection to see better, but only for the convenience of seeing more, and even that it is impossible to see more than one object at a time distinctly:

in so that this convenience, of seeing several others confusedly, is mainly useful only in order to know towards which side one will have to turn one’s eyes afterwards to look at the one among them that one wishes to better consider:

and c This is what nature has provided so much that it is impossible for art to add anything to it; even quite the contrary, especially since, by means of a few glasses, one increases the size of the lineaments of the image which is imprinted at the bottom of the eye; especially as it represents fewer objects, because the space it occupies cannot be increased in any way, except perhaps very little by turning it upside down, which I judge be rejected for other reasons.

But it is easy, if the objects are accessible, to put the one you want to look at where it can be seen most distinctly through the telescope; and, if they are inaccessible, to put the telescope on a machine which is used to turn it easily towards any determined place that one wishes. And so we shall lack nothing of what makes this fourth condition most significant.

For the rest, so that I do not omit anything here, I still have to warn you that the defects of the eye, which consist in the fact that one cannot sufficiently change

The shape of the crystalline humor or the size of the sloe is gradually diminished and corrected by use.

because this crystalline humor and the skin which contains this sloe being real muscles, their functions are facilitated and increased when they are exercised, thus than those of all the other muscles in our body.

This is why:

- hunters and sailors get the power to see afar by looking at very distant objects

- engravers and craftsmen of subtle works get the power to see details by looking at very close ones

Indians can gaze at the sun because their pupils shrank more than ours by often gazing at very bright objects.