What is Light?

5 minutes • 895 words

Table of contents

The whole conduct of our life depends on our senses.

- Of these, sight is the most universal and most noble.

The inventions which increase its power are the most useful.

- The recent invention of lenses increases it the most.

- This is proven by the new stars that they have revealed.

They have given us new knowledge of nature much greater and more perfect than what our forefathers had.

But, to the shame of our sciences, this invention was first found only by experience and fortune.

Around 30 years ago, a man named Jacques Metius, from the town of Alcmar in Holland, he had several glasses of various shapes.

- He had never studied in his life.

- His father and brother made a profession of mathematics.

He had a particular pleasure in making burning mirrors and glasses.

He luckily looked through 2 glasses:

- One glass was a little thicker in the middle than at the ends

- The other, on the contrary, was much thicker at the extremities than in the middle

He applied them so happily to the two ends of a pipe and made the first telescope.

And so, telescopes were made from this pattern without anyone knowing the shapes that these glasses must have.

Many good minds have cultivated this subject very much.

- They have found several things in optics which are worth more than what the ancients left us.

Difficult inventions are not perfected on the first try.

The execution of the things that I will say depends on the industry of the unschooled craftsmen. And so, I will try to make myself intelligible to everyone, and omit nothing.

This is why I will begin with the explanation of light and its rays. Then I will briefly describe the parts of the eye. I will say how vision takes place.

I will use 3 comparisons to explain the properties of light, both the obvious and subtle.

The suppositions of astronomers are almost all false or uncertain.

- We can draw from them several very true and assured suppositions based on their various observations.

1. Light as a Carrier (Medium)

While walking at night without a torch through difficult places, you might use a stick to guide you. This lets you feel the various objects around you, distinguishing them as trees, stones, sand, water, grass, mud, etc.

This kind of feeling is a little confused and obscure to those who are not used to it.

- But those who are born blind have used it all their lives.

You could say that their staff is their sixth sense organ given to them in the absence of sight.

Light is similar to this. Light is the carrier of a certain movement or a very prompt and lively action which passes towards our eyes from a luminous body, through the air and other bodies.

2. Light as Grape Juice (Moving Fluid-Waves)

Almost all philosophers admit that there is no void in nature.

All the bodies which we perceive around us have several pores which are necessarily filled with some very subtle and very fluid matter, which I call the fire-aether. This fire-aether matter extends without interruption from the stars to us.

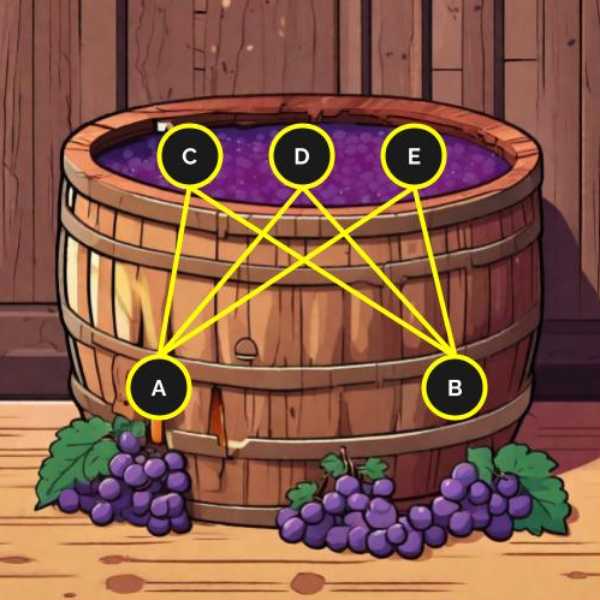

Let us suppose a wooden vat of very mashed grapes and grape juice with 2 holes A and B through which the juice can flow.

The juice in the vat is that pure fire-aether. The crushed grapes are the coarser and less fluid kinds of fire-aether.

The juice around C D E, tend to go in a straight line through the hole A and B when those holes are opened.

Their juice-movements do not hinder the other juices nor by the clusters of crushed grapes*.

*Superphysics Note: The crushed grapes are electrons and other electromagnetic particles like muons.

Those clusters support each other and do not go to holes A and B. Instead, they are moved in other ways by those feet that crush them.

The fire-aether bodies move in other ways, similar to our physical air. They are almost always agitated by some wind.

Sometimes, they have no movement, such as in glass or crystal*.

*Superphysics Note: This is the foundation of our proposed crystal computing where light is the carrier of data that is stopped in glass

Actual Movement Versus the Inclination to Move

It is necessary to distinguish between:

- actual movement and

- the inclination to move.

The inclination to move is expressed as the grape juice at C tending towards B and A without actually moving towards them.

The actual movement is expressed as the grape juice at C actually moving towards B and A but are hindered by the grape clusters that are between them.

In the same way, we are concerned with the actual movement of luminous bodies more than their theoretical movement. This is why you must think of the rays of this light as mere lines along which this movement-action tends.

It follows that there are an infinity of such rays that come from all points of the luminous bodies, towards all points which they shine on.

There is an infinity of straight lines, along with their actions, coming from surface CDE going towards A and B without hindering each other.

Thus, all the parts of the fire-aether that are touched by the side of the Sun facing us tend in a straight line towards our eyes when we open them.