Thunder, Whirlwinds, and Lightning

Table of Contents

There are usually exhalations [ionized air] mixed among these vapors, which cannot be driven as far as them by the cloud.

This is because their particles are less solid and have more irregular shapes.

They become separated from them by the air’s agitation. This is similar to how butter is separated from the buttermilk by beating the cream.

In this way, they assemble in various heaps.

- These float always as high as possible against the cloud.

- These finally come to be attached to the ropes and masts of the ships, when it finishes descending.

There being ignited by this violent agitation, they compose these fires named Saint Elmo’s, which console the sailors, and make them hope for good weather.

Often, these storms are in their greatest force towards the end.

There may be several clouds one above the other, under each of which there are such fires.

This is why the ancients, seeing only one, which they called Helen’s star, esteemed it of bad omen, as if they had still then waited for the height of the storm.

Instead of which when they saw two, which they called Castor and Pollux, they took them for a good omen.

For it was ordinarily the most they saw, except perhaps when the storm was extraordinarily great they saw three, and esteemed them also on this account of bad omen.

However, I have heard our sailors say that they sometimes see 4-5 of them perhaps because:

- their ships are larger and have more masts than those of the ancients, or

- they travel where exhalations are more frequent.

Thunder, whirlwinds, and lightning

There are storms that are accompanied by thunder, whirlwinds, and lightning.

These are caused by several clouds one being above the other.

Sometimes, the highest descends very suddenly on the lowest.

The two clouds A and B are composed only of very decompressed and extended snow.

There is a hotter air around the upper A, than around the lower B.

The heat of this air can condense and weigh it down little by little.

It can make the highest of its particles, beginning the first to descend, to beat down or drag with them a quantity of others, which will also fall all together with a great noise on the lower one.

In the Alps in May, I saw snow heated and weighed down by the sun.

- This created avalanches with the slightest movement of air.

- They also produced the sound of thunder resounding in the valleys.

This is why it thunders more rarely in these regions in winter than in summer.

For so much heat does not easily reach the highest clouds then, to dissolve them.

And why, when during the great heats, after a North wind which lasts very little, one feels again a damp and stifling heat, it is a sign that it will soon follow thunder.

It is a sign that this north wind has passed against the earth and has driven the heat towards the place of the air where the highest clouds form.

Being then driven away, towards that where the lowest form, by the dilation of the lower air which the hot vapors it contains cause, not only the highest by condensing should descend, but also the lowest remaining very rare, and even being as if raised and repelled by this dilation of the lower air, should resist them in such a way that often they can prevent any part of it from falling to the ground.

This makes a noise which becomes louder from the resonance of the air and the falling snow, than is that of avalanches.

Lightning and Whirlwinds

Then note also that from this alone, that the parts of the upper clouds fall all together, or one after the other, or faster, or more slowly;

The lower ones are more or less large, and thick, and resist more or less strongly, all the different sounds of thunder can easily be caused.

For the differences of lightning, whirlwinds, and lightning, they depend only on the nature of the exhalations that are found in the space that is between two clouds, and on the way that the upper falls on the other.

For if there have been great heats and droughts, so that this space contains a quantity of very subtle exhalations, and very disposed to ignite, the upper cloud cannot be almost so small, nor descend so slowly, that driving away the air which is between it and the lower, it does not make an éclair come out, that is to say, a light flame which dissipates itself at the same time. So that one can then see such lightning without hearing any noise of thunder; And even also sometimes without the clouds being thick enough to be visible.

As on the contrary if there are no exhalations in the air that are proper to ignite, one can hear the noise of thunder without any lightning appearing for that. And when the highest cloud falls only by pieces that follow each other, it causes only lightning and thunder; but when it falls whole and fast enough, it can cause whirlwinds and lightning with it.

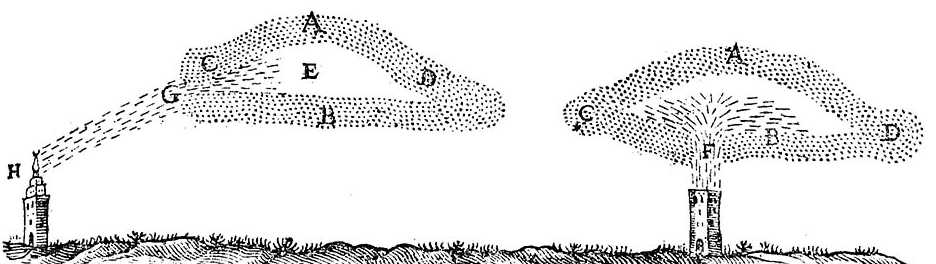

Its extremities, such as C and D, must lower a little faster than the middle. This is because the air that is below has less distance to travel to get out. And so it yields to them more easily.

Thus they come to touch the lower cloud instead of the middle. This encloses a lot of air between them, as we see here towards E.

This air is pressed and driven with great force by this middle of the upper cloud which continues to descend. It necessarily either:

- breaks the lower one to escape, as we see towards F; or

- open one of its extremities, as we see towards G.

When it has thus broken this cloud, it descends with great force towards the earth, then rises again in a whirlwind, because it finds resistance on all sides, which prevents it from continuing its movement in a straight line, as fast as its agitation requires.

Thus it composes a whirlwind; which may not be accompanied by lightning or lightning, if there are no exhalations in this air that are proper to ignite;

But when there are some, they all gather in a heap, and being driven very impetuously with this air towards the earth, they compose lightning.

This lightning can burn clothes and shave hair without harming the body, if these exhalations, which usually have the smell of sulfur, are only greasy and oily, so that they compose a light flame which only attaches to bodies that are easy to burn.

On the contrary, it can break bones without damaging the flesh, or melt the sword without spoiling the scabbard, if these exhalations being very subtle and penetrating, only participate in the nature of volatile salts or strong waters, by which means making no effort against bodies that yield to them, they break and dissolve all those which make them a lot of resistance. As we see strong water dissolve the hardest metals, and do not act against wax.