Air and Winds

Table of Contents

“Air” is any invisible and intangible substance.

“Wind” is any perceptible movement of air.

Water is said to turn into air when it is greatly decompressed and changed into very subtle vapor.

But the air that we breathe is mostly composed of particles that have shapes very different from, and finer than, those of water.

Therefore, the air being expelled from a bellows or propelled by a fan is called wind.

The broader winds which prevail over the sea and land are usually just the movement of vapors that expand.

By expanding, they spread out and move to wherever they find more room.

Similarly, as seen in these spheres called Aeolipiles, a little water vaporizing into steam creates a wind strong and large enough because of the tiny matter that it comprises.

This artificial wind can greatly help us understand these natural ones, so I will explain it here.

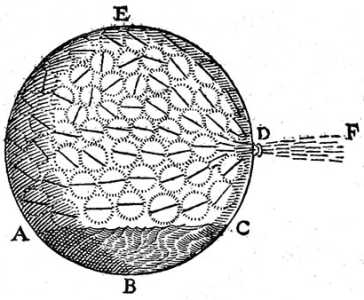

ABCDE is a hollow sphere made of copper or similar material. It is completely closed except for a very small opening marked D.

The part of this sphere ABC is filled with water. The other part AEC is empty, containing only air.

It is placed over fire. The heat causes the water molecules to move. Many rise above the surface AC where they:

- spread out

- swirl around

- push against each other

- try to move apart.

Some escape through the hole D, creating a wind that blows towards F.

New particles of this water are constantly being heated and rise above the surface AC.

- They spread and move apart from each other as they exit through the hole

D.

This wind continues until:

- all the water in the sphere is evaporated, or

- the heat causing the evaporation ceases.

The ordinary winds form in the same way as this one, with 2 differences.

- Their vapors do not just rise from the surface of water, as in this sphere, but also from moist earth, snow, and clouds.

Therefore, they usually emerge in greater abundance than from pure water, because their particles are already mostly separated and disjointed, and thus easier to separate further.

- These vapors, unlike those in an Æolipile, cannot be contained in the air.

Rather, they are hindered from spreading evenly in all directions by the resistance of other vapors, clouds, mountains, or by winds blowing towards their location.

However, elsewhere in the atmosphere, other vapors often thicken and contract at the same time the former expand, directing them towards the space left by the latter.

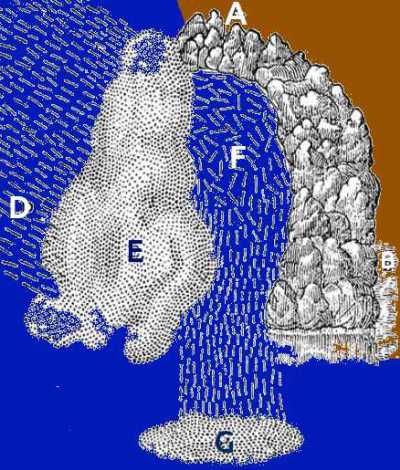

For example, imagine that there are currently numerous vapors at the point in the air marked F, expanding and occupying a much larger space than they currently occupy.

Simultaneously, there are others at G, condensing and converting into water or snow, leaving most of the space they previously occupied.

Those vapors towards F will move towards G, thus forming a wind that blows in that direction.

They are hindered from spreading towards A and B by high mountains there, and towards E because the air is pressurized and condensed by another wind blowing from C to D.

Moreover, there are clouds above them that prevent them from spreading higher into the sky.

When vapors move in this way from one place to another, they carry or push ahead all the air they encounter on their path, and all the exhalations along with it.

Thus, although they almost single-handedly cause the winds, they do not solely constitute them.

Also, the expansion and condensation of these exhalations and air can contribute to the production of these winds, but this contribution is minimal compared to the expansion and condensation of vapors.

Air, when expanded, occupies only about 2-3 times more space than when moderately condensed. Whereas vapors occupy more than 2-3,000 times more space.

Exhalations do not expand, meaning they do not separate from terrestrial bodies, except with great heat.

They can hardly ever be as condensed again by cold as they were before. In contrast, very little heat is needed to expand water into vapor, and very little cold to turn vapors back into water.