Making Ice with Salt and Crushed Ice

Table of Contents

Salt is mixed with an equal quantity of snow or crushed ice all around a vase full of fresh water.

This salt and snow melt together, causing the water enclosed in the vase to turn into ice.

This is because the air-aether that was around the water particles are coarser or less subtle than the snow particles.

- And so they have more force.

The snow particles roll around the salt particles while melting.

The air-aether in the fresh water finds it easier to move in the pores of salt water.

- And so it constantly passes to the body where its movement is least hindered.

And so the air-aether in the snow enters the water to replace that which comes out.

- It causes the water to freeze because it does not have enough force to maintain the agitation of this water.

The Rigidity of Salt

One of the main qualities of salt particles is that they are highly fixed. They cannot be raised as vapor like fresh water particles.

This is because they are:

- larger and heavier

- longer and straighter

This means that when saltwater is airborne, its particles point downwards, perpendicular to the earth.

- This lets them divide the air easily when rising or falling.

Fresh water particles cannot do this because they fold easily.

- They can never remain completely straight unless they spin rapidly.

But salt particles can hardly ever spin in this way because they bump into each other without being able to bend to let each other pass.

- And so they are forced to stop immediately [because they are rigid].

Airborne saltwater particles:

- must fall if they are pointed downwards.

- rise if they are pointed sideways

It acts less precisely because the amount of air resisting their point is smaller than that which would resist their length; whereas their weight, always being equal, acts more as this air resistance is smaller.

Sea water softens when it passes through sand. This is because the salt particles are unable to bend.

And so, they cannot flow as the fresh water particles do through the small winding paths around the grains of this sand.

- This is why fountains and rivers should not be salty – because they are composed only of waters raised as vapors or passed through much sand.

All these fresh waters going into the sea should do not make it larger or less salty. This is because as much other water constantly comes out.

- Some rise into the air, changing into vapors.

- They then fall as rain or snow on the earth.

- But mostly, they penetrate through underground conduits to go below the mountains.

- From there, the heat in the earth raises them as vapor toward their summits filling the sources of fountains and rivers there.

Sea water should be saltier in the equator than near the poles because the sun has more force there.

- This causes many vapors to rise.

- These do not fall back in the same places where they rose.

- Usually, they fall closer to the poles.

Sea water:

- is less suitable for extinguishing flames than river water.

- sparkles at night when agitated

This is because the salt particles:

- are easily shaken

- are almost suspended among the fresh water particles

- have much force when thus shaken

This is because they are straight and inflexible.

- This makes them increase the flame and cause sparks by leaping out of the water where they are.

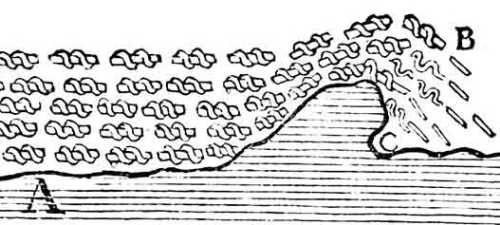

The sea at A is forcefully pushed towards C. There it meets a sandbank or some other obstacle that makes it rise toward B.

This jolts the salt particles and makes the first ones that come into the air detach from those of the fresh water holding them entwined.

They find themselves alone at B at a certain distance from each other. They generate sparks there, quite similar to those that come out of stones when struck.

For this effect:

- these salt particles should be very straight and slippery so that they can more easily separate from those of the fresh water.

- This is why neither brine nor seawater that has been kept for a long time in a container is suitable.

- the fresh water particles should not embrace the salt particles too tightly. This is why:

- these sparks appear more when it is hot than when it is cold; and that the agitation of the sea is strong enough:

- not all its waves emit fire;

- the salt parts should move sharply like arrows and not sideways

- This is why not all droplets splashing out of the same water light up in the same way.