Vapors and Exhalations

Table of Contents

Superphysics Note

The sun or other causes can agitate the air-aether [space] and small earth-aether [matter] particles inside the pores of material bodies.

- The earth-aether particles are more strongly agitated than the air-aether.

The following earth-aether particles are easily separable:

- the small ones

- those shaped or situated in a separable way

This causes them to scatter and rise into the air simply because they cannot find any other place to go.

It is not because:

- they have an inherent inclination to ascend*

- the sun exerts a force drawing them upwards

Superphysics Note

This is similar to how dust in a field rises when it is pushed and agitated by the feet people passing by, making them go up into the air.

- More dust rises when more people walk on them.

The action of the sun raises vapors quite high, since the sun always shines over half of the earth and stays there all day.

Vapors Versus Exhalations

These small particles raised into the air by the sun should mostly have the shape of water.

- This is because they are the most easily separable from the bodies that they are in.

I call these particles as vapors.

- This is to distinguish them from those with more irregular shapes, which I will call “exhalations”, as I know of no better term.

Exhalations include spirits or essential oils.

- These have nearly the same shape as water particles but are finer or subtler.

- This makes them easily ignite.

I will exclude the earth-aether particles that make up the physical air that are:

- divided into several branches

- so subtle

| Physics Name | Cartesian Name |

|---|---|

| Water Vapor | Vapors |

| Ionized Air | Exhalations |

| Hydrocarbons | Spirit-Exhalations |

There are earth-aether particles [carbon] that are a bit coarser and also divided into branches.

- They cannot leave the hard bodies which they are a part of by themselves.

- But they can be driven by fire, such as the fire which drives them out as smoke.

When water slips into their pores, the water can often release these earth-aether particles and carry them up with it.

- This happens in the same way that the wind, passing through a hedge, carries away the leaves or straw entwined among its branches.

Expansion of Water-Vapor from Heat or Agitation

Vapors always occupy much more space than water even if they are made of the same small particles [have more space particles].

Water particles only move strongly enough to bend, intertwine, and slide against each other, as represented at A.

When they become vapor, their agitation is so great that they quickly turn around in all directions and stretch out to their full length.* [have maximum space particles from heat particles]

- Each has the force to push away all its similar particles that tend to enter its small sphere.

- This is represented at

B.

Superphysics Note

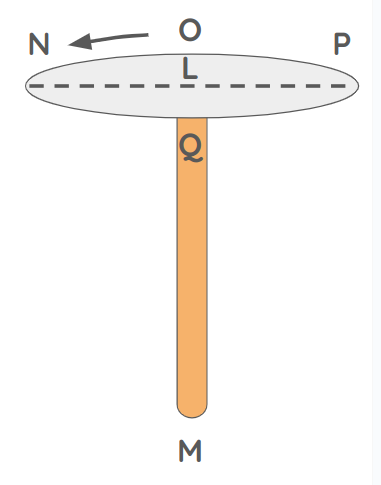

This is similar to how, if you spin the pivot LM fast enough, cord NP will stand in the air, straight and stretched.

- It will occupy all the space within the circle

NOPQ. In this way, bodies within that circle are immediately struck and driven out.

However, if you move it slowly, it will coil around the pivot itself. It will no longer occupy as much space.

These vapors can be:

- compressed or expanded

- hot or cold

- transparent or opaque

- humid or dry

When their particles get cooler, they no longer stretch out in a straight line.

- They begin to bend and contract as shown as

CandD.

Vapors become denser or more compressed in the 3 scenarios:

-

When the vapors cool down and are compressed as seen near

CandD. -

When the vapors are squeezed between mountains or various winds or under some clouds.

- This prevents them from expanding into as much space as their agitation requires.

- This is also seen at

E.

- When they use most of their agitation to move together in the same direction.

- And so they no longer whirl around as strongly as usual, as seen at

F. - Sometimes they emerge from space

E, generating a wind that blows towardsG.

If the vapor that is near E is as agitated as that near B, then it will be much hotter.

- This is because its particles, being more tightly packed, have more force.

- This is similar to how the heat of glowing iron is much more intense than that of embers or flame.

This is why we often feel a stronger and more stifling heat in summer when the air is calm and equally pressed from all sides to create humidity and rainclouds, than when it is clearer and more serene.

The vapor at C is colder than that at B, even though its particles are slightly more compressed.

- This is because they are much less agitated. [has less heat particles]

Conversely, the vapor at D is hotter because its particles are much more compressed, but only slightly less agitated [than B].

Descartes’ Non-Brownian Motion Versus Physics Entrainment*

Superphysics Note

The vapor at F is colder than that at E even if its particles have the same compression and agitation as E.

- This is because they are moving in the same direction.

- This prevents them from shaking the small particles of other bodies as much.

- This is like how a strong wind that always blows in the same direction does not shake the leaves and branches of a forest as much as a weaker one that is less steady.

Heat consists in this agitation of the tiny earth-aether particles.

You can experience this if you blow hard on your fingers held together.

The breath coming out of your mouth will seem cold over the top of your hand.

- This is because it moves very fast and with even force.

- This causes little agitation [low volume of heat particles]

Whereas, you will feel it quite warm between your fingers.

- This is because it moves more unevenly and slowly agitating their tiny particles more.

In the same way, we feel our breath is:

- warm when blowing with the mouth wide open,

- cold when blowing with it almost closed.

This is why:

- violent winds are cold

- warm winds are slow [and chaotic]