Things That Move The Pineal Gland

Table of Contents

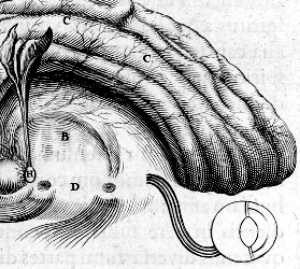

The pineal gland is composed of a very soft material – a substance that is not united with the substance of the brain everywhere, but is only attached to it by small arteries.

These arteries have flexible and pliable walls that suspend the gland like a balance.

- It is influenced by the force of the blood pushed into it by the heartbeat.

This allows the gland to lean in one direction easily.

- This then directs the spirits emerging from it to flow into certain parts of the brain

In this way, it can easily incline towards itself or elsewhere.

- When it inclines, it channels the spirits that emanate from it to flow more towards certain parts of the brain.

Two things can move that gland that are not included as the forces of the soul:

- The variation among the particles of the spirits that emerge from it

The spirits would flow evenly through all the gland’s pores if:

- all the spirits had the same strength

- there were no other factors causing the gland to lean one way or another

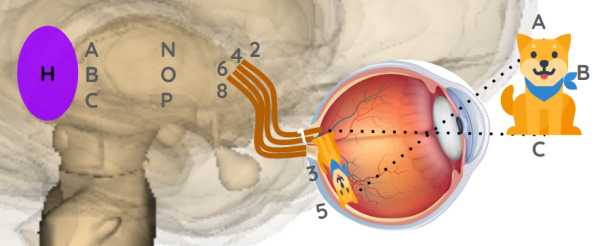

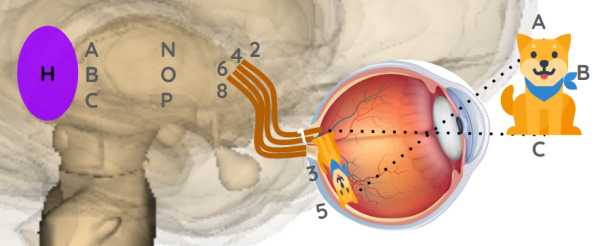

In such a case, the gland would be perfectly balanced and immobile at the brain’s center, as shown below.

A body attached to threads and lifted by the smoke coming out of a chimney would continually fluctuate depending on how the smoke acted on it.

So too, the particles of those spirits that uplift and sustain the pineal gland always vary slightly.

- These lean the gland to one side, then another, as seen below.

The center H is farther from the center of the brain, marked with the letter O.

The extremities of the arteries that sustain it are also farther from the center and so curved that almost all the spirits go through the surface A, B, C, to tubes 2, 4, 6.

- This opens those tubes which look more directly there than the other tubes.

The primary effect of this is that the spirits emerging from specific parts of the gland’s surface can turn those tubes into the direction where those spirits came from.

This, in turn, causes the body parts connected to those tubes to move towards the locations that correspond to whatever those parts of the gland’s surface are associated with.

The idea of a body-part’s motion is determined solely by how the spirits exit the gland, such that the body-part’s motion is created from that idea.

This same process lets the soul perceive the arm turning towards B.

All the points which the tubes can turn towards correspond to all the locations to which the arm 7 can move.

In this way, the arm’s position relative to object B is due solely to the alignment of its tube towards point b.

If, however, the spirits change their course and re-directed the tube to C, then the filaments of 7 would change their configuration accordingly.

- They would dilate brain pores around

dand others in turn. - As a result, the spirits passing through these pores into the corresponding muscles would immediately shift the arm towards object

C.

The spirits entering through tube 8 causes the arm to turn towards B or C.

If another cause moves the arm towards B or C, it would also direct tubes 8 or d to turn towards b or c.

This would then form the idea of this movement.

- This is unless the attention was distracted.

Distraction means that gland H was not impeded by a stronger action preventing it from leaning towards 8.

Thus:

- each brain tube is connected to a specific body part.

- each point on the surface of the pineal gland corresponds to a particular position to which those body-parts can be moved.

Consequently, the movement of the limbs and their ideas mutually and reciprocally cause each other without contradiction.

This is why when both the eye and the other sense-organs are turned to the same object, only one idea is formed in its brain, not multiple ideas.

This is because the same points on the pineal gland’s surface from which the spirits emerge can direct them to various tubes that move different body parts in order to align with the same object.

Here, the spirits emanate from point b alone then go to tubes 4 and 8.

This turns both eyes and the right arm towards object B.