The Surface of the Brain

Table of Contents

28. The pores of the brain are like the gaps between the threads of linen

The whole brain is a texture arranged in a peculiar manner.

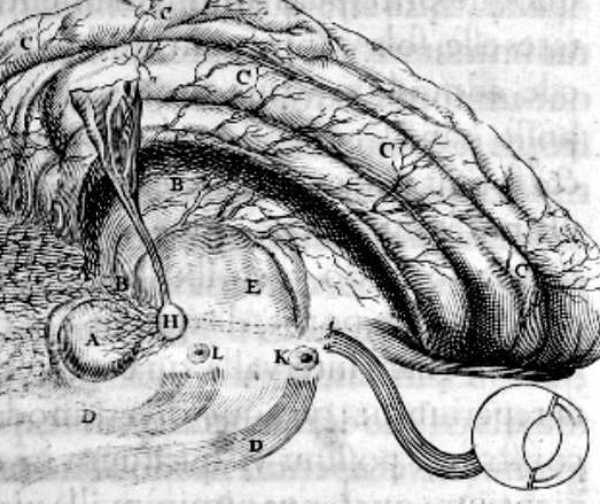

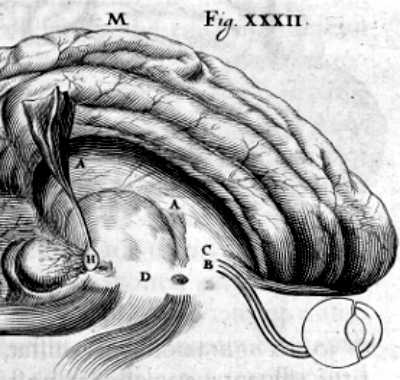

29. The surface AA faces the cavities EE

It is like a fairly expanded, dense, and intricately woven plexus, resembling a mesh of crosshatched texture.

The Nerve Fibers or Filaments

Each of its filaments is a tube through which the spirits flow.

The spirits constantly look towards pineal gland H where they came from.

From these filaments, they can easily turn to the different points of the pineal gland.

- For example, these are differently oriented in figure 31 than in 32.

There are countless very delicate filaments that emerge from the pineal gland.

- Some are ordinarily longer than others.

However, after these filaments have been interwoven in various ways throughout space B, the longer ones descend to D.

There they form the medulla of the nerves, which are then distributed throughout all the limbs.

These filaments can be easily folded and bent in various ways solely by the force of the spirits that touch them.

- This is as if they were made of lead or wax.

- Therefore, they always retain the fold to which they were last affected until another is impressed upon them by spirits acting in the opposite manner.

These pores are the spaces between these filaments.

- These can be extended and contracted in various ways by the force of the spirits that enter them, depending on whether that force is stronger or weaker.

The shorter filaments of the pineal gland are received into space CC, where each terminates at the ends of certain vessels there, through which the brain receives nourishment.