Sight

Table of Contents

18. The sense of sight depends on two nerves composed of a vast number of extremely mobile capillaries

These convey those various actions of the air-aether to the brain. This provides the soul with the opportunity to conceive various ideas of colors and light.

The structure of the eye is very useful and necessary for the air-aether.

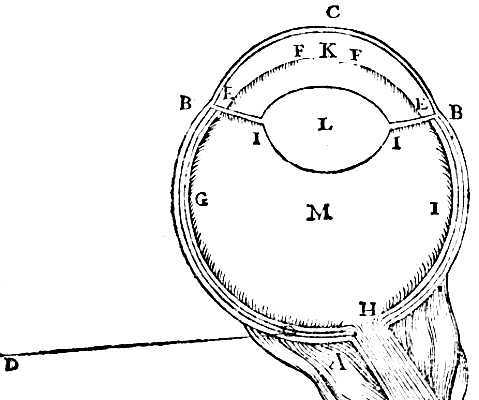

A, B, C in Fig. 15 is a thick and hard membrane forming a kind of round vessel and constituting the receptacle of the other parts of the eye.

D, E, F is a thinner membrane spread within the former like the covering of a room.

G, H, I is the nerve commonly called the optic nerve. Its capillaries H, I, HI spread throughout the entire space from A, B, H to I, covering the entire back of the eye.

K, L, M are 3 very translucent fluids, stretching these tunics from all sides, in the shape depicted here.

In the first membrane, the part BCB is translucent and more convex. Refraction of incident rays occurs towards the perpendicular.

The inner surface of the second membrane, part EF facing the back of the eye, is entirely dark and black.

It has a small round hole in the middle of the front part, appearing darkest to observers, which we call the pupil.

However, this gap is not always the same size.

But the second little membrane EF is attached to a very clear fluid. It resembles a small muscle.

When directed by the brain, it contracts or dilates as required by usage.

The shape of humor L is called crystalline.

It is similar to the glasses described Dioptrics by which all rays coming from one point are collected at another point.

It is made of a less soft and more consistent material. Consequently, it causes greater refraction than the other two humors that surround it.

EN are numerous black filaments protruding inward from the membrane DEF, which surrounds the crystalline humor on all sides.

They are like small tendons. Their operation makes the crystalline humor immediately more convex or flatter as our vision is directed to nearby or distant objects, thus slightly altering the entire shape of the eye.

Finally, OO are 6-7 muscles attached externally to the eye, by which it can be easily moved in any direction.

However, the membrane BCB and the 3 humors KLM are very translucent. They do not hinder the rays entering through the pupil from penetrating to the back of the eye where the nerve is.

They also affect the nerve no less easily than if it were completely bare and not covered by any such tunics.

Moreover, they protect the nerve against injuries from air and other bodies, which, if they acted upon it, would injure it with little effort.

Furthermore, they preserve it so tender and accurate that it is less surprising that it can be moved by actions as slightly perceptible as those we call colors.