Hearing and Harmony

Table of Contents

16. The filaments that make up the ears are not as thin as those preceding them

They are arranged in the inner concavity of the ears.

- They are easily and uniformly moved by tremulous motions caused by the external air.

This air presses on the thin membrane stretched over the openings of these concavities.

These tremulous impulses reach all the way to the brain through the nerves.

- This allows the soul to conceive the idea of sounds.

An impulse will present to the hearing only an indistinct murmur that will perish in a moment.

The ear is stimulated by the size of the the impulse.

When several impulses follow one another:

- the equality of these impulses will make them sound sweeter to the soul

- the inequality will make them sound harsher.

They will sound higher when the impulses follow each other promptly.

They will sound lower when they follow less promptly.

If by half or a third or a quarter or a fifth part, etc., one follows the other more promptly, they will produce a sound which will be higher by an octave, or a fifth, or a fourth, or a major third, etc.

The tones will agree or disagree depending on:

- whether the similarity or proportion is greater or lesser, or

- whether the intervals between the impulses are more or less equal.

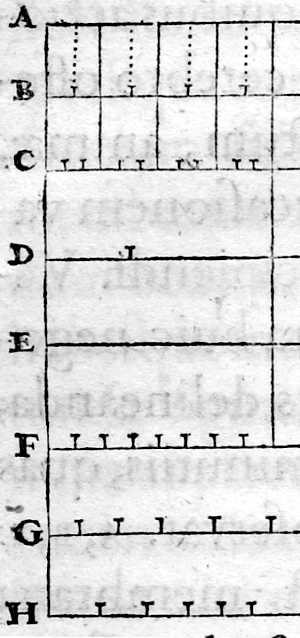

For example, the divisions A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H represent small impulses composing various sounds. Those represented by the lines G and H will not be as pleasing to our ears as others.

This is similar to the roughness of a stone being less pleasing to the touch than the smoothness of a polished mirror.

Brepresents a sound higher by an octave thanACrepresents a fifthDrepresents a fourthErepresents a major thirdFrepresents an even higher sound

A and B, or A B C, or A B D, or A B E, or even A B C E, harmonize better than A and F, or A G D,orA D E`, etc.

17. This is how the soul, which inhabits the machine I, can be pleased by Music

It shows how it can be made far more perfect, if only we observe that sweeter things are not always more pleasing to the senses absolutely, but only those that affect the senses with a more moderate titillation.

Just as salt and vinegar often give greater pleasure to the tongue than sweet water.

This is why Music uses thirds, sixths, and sometimes even dissonances, no less than unisons, octaves, and fifths.