Problems that can be constructed using only circles and straight lines

Table of Contents

This treatise can only be understood by those who are familiar with Geometry.

All Geometry problems can be easily reduced to such terms that it is only necessary to know the lengths of certain straight lines to construct them.

All Arithmetic is composed of only four or five operations:

- Addition

- Subtraction

- Multiplication

- Division

- Extraction of roots

The last can be considered as a type of Division.

Similarly, in Geometry, one only needs to add or subtract lines to or from the lines being sought to make them known.

Or having one line, which I will call unity to better relate it to numbers, and which can usually be chosen at will, then having 2 other lines, find a 4th line that is to one of these two as the other is to unity, which is the same as Multiplication.

Or find a 4th line that is to one of these 2 as unity is to the other, which is the same as Division.

Or finally, find one, two, or several mean proportionals between unity and some other line, which is the same as extracting the square root, or cube root, etc.

Multiplication

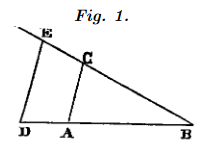

For example, let AB be unity.

Suppose it is necessary to multiply BD by BC.

I have only to join points A and C, then draw DE parallel to CA.

BE is the product of this Multiplication.

Division

To divide BE by BD, having joined points E and D, I draw AC parallel to DE``, and BC` is the result of this division.

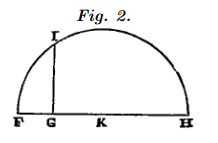

Extraction of the square root

Or if it is necessary to extract the square root of GH, I add to it in a straight line FG, which is unity, and divide FH into two equal parts at point K.

From center K, I draw the circle FIH, then raise from point G a straight line to I, at right angles to FH, and GI is the root sought.

I will discuss the cube root or others later.

How one can use numbers in Geometry

But often we do not need to actually draw these lines on paper.

We can designate them by a few letters, each by a single one.

As to add the line BD to GH, I name the one a and the other b, and write a + b and a - b to subtract b from a; and ab to multiply them together;

and a/b to divide a by b; and aa or a² to multiply a by itself; and a³ to multiply it once more by a, and so on to infinity;

and √(a² + b²) to extract the square root of a² + b²; and ∛(a³ − b³ + ab²) to extract the cube root of a³ − b³ + ab², and likewise for others.

By a², or b³, or similar expressions, I generally understand only simple lines, even though I use the conventional names of algebra and call them squares or cubes, etc.

It should also be noted that all parts of the same line must generally be expressed with the same number of dimensions when the unit is not determined in the question—for example, a³ contains as many dimensions as ab² or b³, from which is composed the line I have named…

…but this is not the case when the unit is determined, because it can be implied wherever there are too many or too few dimensions: for instance, if one must take the cube root of a²b² − b, one must consider that the quantity a²b² is divided once by the unit, and that the other quantity b is multiplied twice by the same.

Finally, in order not to forget the names of these lines, one must always keep a separate record as they are introduced or changed, writing for example:

A B = 1, c’est-à-dire A B égal à 1 GH = a BD = b etc